Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com

Dudley Field Malone at the time of his appointment as

US Collector of Customs for the Port of New York, 1913.

(Library of Congress).

As mentioned on the Deadly Cargo page of this website, the British Army was firing more shells per week than Britain’s armaments

factories produced. The British therefore had a truly desperate need to import munitions of war. The British imported munitions from

Russia already, but this simply wasn’t enough to meet demand, so the British Government turned to the then neutral United States as

well.

The outbreak of the European War in August 1914 had produced internationally economically recessive times of course. By the end of

the first quarter of 1915, that recession was being felt. The American President, Woodrow Wilson, clearly wanted this munitions export

business, as it was a multi-million dollar trade and therefore a much-needed shot in the arm for American industry. Furthermore, he

was up for re-election in 1916, but however he secured the deal, he still had to be outwardly seen as upholding US neutrality and the

only way to get these American-made munitions to England was across the Atlantic Ocean, by ship.

The trouble was that the British needed ready-made munitions urgently. Just sending the components for British factories to produce

shells from was not an option. The British factories were critically short on output. British reserve stocks were down to about a three

month period to exhaustion and even that narrow margin was getting narrower by the week. Regular cargo ships usually took about

ten days to cross the Atlantic. Ten days might suffice for more non-urgent items, but ready-to-use munitions just had to make it to

England sooner. The fastest ships were the ransatlantic liners of the Cunard and White Star Lines, and others like them, but it wasn’t

legal to ship explosives aboard passenger vessels, for obvious reasons. What was needed was a way to make it legal.

It transpired that it was legal to ship ordinary bullets aboard passenger trains and coastal passenger ships in certain parts of America.

This had come about as the result of an open air demonstration before the Municipal Explosives Commission of New York City a few

years before. A stack of crated pistol ammunition was deliberately set on fire to see if it exploded. It didn’t. It burned fiercely, but out in

the open air, with nothing to confine the burning gases or intensify the heat, it didn’t explode as such. It also helped that the

ammunition used for the demonstration consisted of obsolete, black powder filled cartridges. Suitably impressed by the resultant non

explosion, the MEC of NYC sanctioned the transporting of such NON EXPLOSIVE ammunition on public transport, including

passenger ships, as long as the cases they were in were clearly marked NON EXPLOSIVE. The MEC’s sanctioning was then turned

into the basis for the WHOLESALE EXPORT of munitions from the Port of New York. The Port of New York was of course where the

bulk of the transatlantic liners docked. The relevant legislation was quickly put into place. They’d just made it “legal”, by a thread, but it

was still better, certainly at this stage, if this rather thin veneer wasn’t subjected to too much public scrutiny. Strictly speaking of course,

the cargoes WERE contraband, because munitions ARE explosive. Once again, the demonstration before the MEC, and the outcome

of it, was thoroughly reported in the New York Times.

The British Government placed their munitions import orders with the Admiralty’s Trade Division, who in turn placed the orders with

American businessman J Pierpoint Morgan, owner of the International Mercantile Marine Company. Morgan was officially appointed as

sole purchaser for the British Government’s munitions requirements in January of 1915 and he worked as such on the basis of his

receiving a 1% commission of all order values.

Morgan in turn, used a complex chain of fictitious companies to secure the necessary items. The IMM’s ships and passengers then

became the unwitting carriers of this contraband, assisted by any ships the British Admiralty had any control over or could otherwise

charter. In order to get the vital munitions aboard the chosen passenger ships, it became standard practice to file a less than truthful

manifest with the US Collector of Customs in the Port of New York. This manifest would show a purely general cargo. Later, once each

ship had left US territorial waters, a “Supplemental Manifest” would be filed with the Customs office, listing any “last minute provisions

or cargo items” that had been loaded, though the nature of any obviously suspect consignments would be slightly altered or otherwise

listed.

But what if the Collector of Customs found out?

A far better question is:

What if the Collector of Customs was in on it in the first place?

But why on Earth would the US Collector of Customs acquiesce in such a practice? To issue a ship with a sailing clearance certificate,

which is after all a legal document, knowing it was based on a less than truthful manifest, was surely a criminal offence? Are we talking

Bribery? Corruption? Ignorance? Or even just a conspiracy theory? If it were true, that this Customs Official knew what was going on

and that he willingly took a part in it, surely he’d have ended up in prison sooner or later?

So, who was the US Collector of Customs for the Port of New York in 1915?

That man was Dudley Field Malone.

An active member of the Democrat Party, Dudley Malone was the son of a Philadelphia Democratic Official; William C. Malone and

Rose (McKenny) Malone. He was born on June 3rd 1882.

Malone was put in the office of Collector of Customs for the Port of New York by President Woodrow Wilson in 1913, though Wilson

needed the backing of his friend, New York Senator James A O' Gorman, to secure Malone’s appointment. O' Gorman was very much

the rising star in the New York Democrat camp at that time. He was already on NYC's Legislature Committee and with his appointment

to the Foreign Relations Committee in 1913 O’ Gorman’s influence, especially in New York, was assured. Senator O' Gorman readily

consented to Wilson’s wish, mainly because Dudley Malone had been married to his daughter, May O’ Gorman, for five years at the

time.

Malone was a Lawyer by trade, specialising in Divorce and Probate. He was also very much a personal friend and political ally of

President Wilson's. Both Wilson and Malone often spoke publicly and in the press, in support of each other. Malone went on the

campaign trail with Wilson for the President's 1916 re-election campaign. Being O'Gorman's son-in-law would undoubtedly have been

beneficial on the campaign trail too.

Malone however, had a lot of political and financial skeletons rattling around in his closet: Skeletons that had a nasty habit of exposing

themselves every now and again. Skeletons such as his being under official investigation for aspects of his estate lawyering activities,

in March of 1916. Malone had stood accused of fraudulently hiding assets, possessing dubious "gifts" and other financial irregularities.

This was to be a recurrent theme in his life.

After Wilson's re-election, Malone resigned as Collector of Customs due to a political disagreement with Wilson over the women's

movement, being succeeded as Collector by Byron P Newton in October of 1917. Malone then announced his public support for the

Socialist Morris Hillquit, in his quest to become Mayor of NYC. Malone himself was being publicly attacked in the press at that time by

members of the Roman Catholic Church in Brooklyn, over his politics. Malone’s own arrogance seems to have prevented him from

realising that he was becoming something of a liability to the Democrats by then.

By 1918 however, he was back in the Democrat fold again, fighting the feminist cause in support of Wilson; but not for long. In 1920 he

ran for Governor of New York on the Farmer-Labour Party ticket, earning just 69,908 votes versus 1,335,617 votes for winning

Republican Nathan L. Miller, 1,261,729 for incumbent Democrat Al Smith and 171,907 for the Socialist Joseph Cannon. After this

ignominious defeat, Malone left the Democrats to become an Independent.

In 1921, his wife May O' Gorman, divorced him, and he took another wife, the feminist and writer Doris Stevens. They moved to Paris,

France, where he'd recently set up a Law firm. However, he was soon back home in the States and being sued for malpractice by one

or two of his French clients. In 1929, his second wife also divorced him. He spent most of the early thirties flitting backwards and

forwards between the US and France whilst still being pursued by at least three of his more notable clients over money. He then

married Edna L. Johnson in a London Registry Office in January of 1930. In 1931, he and his third wife went on a cruise to Bermuda,

probably to escape the ever growing number of his clients who were hounding him over money. By 1935, he had filed for bankruptcy,

owing more

than $260,000, though he managed to wriggle out of one of the law suits against him.

In 1943, he played the part of his old friend, WINSTON CHURCHILL, in a propaganda film called Mission to Moscow.

In 1949, he was beaten up at the roadside by two men, which hardly seems surprising at all. He died at Culver City Hospital,

California, in 1950. Ever the social-climber, Dudley Malone seems to have been rather a shady character, to say the least.

So, to return to the question of “What if the US Collector of Customs was in on it in the first place?”

Malone knew exactly what was taking place, but he was instructed to turn a blind eye to the practice. Malone would issue a sailing

clearance certificate for each ship, usually the day before its scheduled departure, based only on what was called a “Loading

Manifest”. Something like the real manifest, the “Supplemental Manifest”, would be filed about three days after each ship had sailed,

when it was too late to do anything about it anyway.

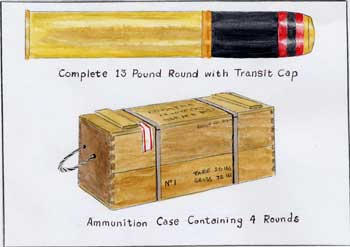

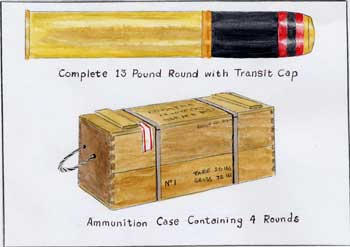

During the outcry over the Lusitania case, Malone was asked by a reporter from the New York Times, in his position as Collector of

Customs, if projectiles such as those used by the Artillery could be classed as explosives. He was quoted in the paper as stating that:

“If no fuse was fitted to them then they would be classified as being NON-EXPLOSIVE. Therefore any such projectiles as might be

loaded aboard a passenger ship would not be illegal under US law, as long as it appeared on the manifest”. In short, he’d been

treating artillery shells as being nothing more than “big bullets” and bullets were what the Municipal Explosives Committee of NYC had

initially sanctioned. If the fuse wasn’t fitted to it,

then the shell, in theory, had no means of detonation. Kapitan-Leutnant Schwieger of course changed that, on Friday 7th May, 1915,

by inadvertently introducing a G6 torpedo amongst 5,000 of these supposedly NON-EXPLOSIVE “big bullets”.

With his good friend Senator James A O' Gorman on New York City's Legislature Committee it was obviously made much easier for

President Wilson to go a step further and get these now miraculously “empty”/NON-EXPLOSIVE” munitions made legal to transport on

transatlantic passenger ships. Of course, Wilson also had another personal friend, O' Gorman's son-in-law, Dudley Malone, whom he’d

personally put at the Head of Customs in New York, who could then "legally" clear these munitions to be loaded onto eastbound

passenger ships. Given Malone’s background, then and since, it would indeed seem highly likely that the wilful and knowing issuing of

sailing clearances on the basis of a less than truthful manifest, would not have been beyond Dudley Malone at all.

One week after the Lusitania disaster, The International Mercantile Marine Company announced in the New York Times that “in future,

IMM ships would no longer carry munitions of war as cargo”. The words in future and no longer should be particularly noted! Despite

this most public statement, liners of the White Star Line, (who were owned by IMM), continued to sail from New York with vast

quantities of war materials in their holds. Their departures and the nature of their cargoes were regularly published in the New York

Times. On December 10th, 1915, seven months after the Lusitania was sunk, the New York Times announced that the White Star Liner

Adriatic had left New York carrying 18,000 tons of war munitions for the Allies. Among the cargo items listed were 5,973 “empty” shells

(NON EXPLOSIVE of course). The ship’s total cargo was valued at $10,000,000. Less than a year later, in August of 1916, the New

York

Times again reported the sailing of another White Star Liner, one of Adriatic’s sisters, the Baltic, carrying 18,500 tons of war munitions

for the Allies. Such reports were usually printed about three days after the ship had left, once their supplemental manifests had been

filed with Malone’s office. That gives an idea of the scale of the munitions shipping operation: TWENTY MILLION DOLLARS worth of

munitions exports, on just those two ships alone, on ONE voyage. It is also worth noting that the Adriatic and the Baltic were both

about one third smaller than the Lusitania.

Another interesting sub-point is that Charles M Schwab, President of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, who manufactured most of the

munitions that were being shipped to Britain on these liners, was himself a regular passenger on both the Lusitania and the

Mauretania.In the wake of the Lusitania disaster, “Champagne Charlie” as he was known, was asked by the New York Times if it was

normal for his munitions products to leave the factory in crates marked NON EXPLOSIVE. He stated that he had no idea, as he wasn’t

often there.In fact, he said; in the week that the Lusitania had been sunk, he’d been away, so he felt he couldn’t possibly comment on

the matter further anyway.

By the end of 1915, the year in which the Lusitania was sunk, exports of American-made munitions to Great Britain had totalled $199,

627, 324. The monthly average for munitions exports during the period 1st Jan 1915 to 1st Jan 1916 was $74, 003, 583. Both of these

figures were proudly announced in the business pages of the New York Times of September 7th 1916. By the time of the US entry into

World War 1 in 1917, it had well and truly passed the $1bn mark. All of it of course, had been sent by ship, and not just from the port of

New York. There were shipments from Boston and Philadelphia too. We’ll leave you to work out what commission J P Morgan had

earned for himself as sole purchasing agent, at 1% of all orders!

Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com

Dudley Field Malone at the time of his appointment as

US Collector of Customs for the Port of New York, 1913.

(Library of Congress).

As mentioned on the Deadly Cargo page of this website, the British

Army was firing more shells per week than Britain’s armaments

factories produced. The British therefore had a truly desperate

need to import munitions of war. The British imported munitions

from Russia already, but this simply wasn’t enough to meet

demand, so the British Government turned to the then neutral

United States as well.

The outbreak of the European War in August 1914 had produced

internationally economically recessive times of course. By the end

of the first quarter of 1915, that recession was being felt. The

American President, Woodrow Wilson, clearly wanted this

munitions export business, as it was a multi-million dollar trade and

therefore a much-needed shot in the arm for American industry.

Furthermore, he was up for re-election in 1916, but however he

secured the deal, he still had to be outwardly seen as upholding US

neutrality and the only way to get these American-made munitions

to England was across the Atlantic Ocean, by ship.

The trouble was that the British needed ready-made munitions

urgently. Just sending the components for British factories to

produce shells from was not an option. The British factories were

critically short on output. British reserve stocks were down to about

a three month period to exhaustion and even that narrow margin

was getting narrower by the week. Regular cargo ships usually took

about ten days to cross the Atlantic. Ten days might suffice for more

non-urgent items, but ready-to-use munitions just had to make it to

England sooner. The fastest ships were the transatlantic liners of

the Cunard and White Star Lines, and others like them, but it wasn’t

legal to ship explosives aboard passenger vessels, for obvious

reasons. What was needed was a way to make it legal.

It transpired that it was legal to ship ordinary bullets aboard

passenger trains and coastal passenger ships in certain parts of

America. This had come about as the result of an open air

demonstration before the Municipal Explosives Commission of New

York City a few years before. A stack of crated pistol ammunition

was deliberately set on fire to see if it exploded. It didn’t. It burned

fiercely, but out in the open air, with nothing to confine the burning

gases or intensify the heat, it didn’t explode as such. It also helped

that the ammunition used for the demonstration consisted of

obsolete, black powder filled cartridges. Suitably impressed by the

resultant non explosion, the MEC of NYC sanctioned the

transporting of such NON EXPLOSIVE ammunition on public

transport, including passenger ships, as long as the cases they

were in were clearly marked NON EXPLOSIVE. The MEC’s

sanctioning was then turned into the basis for the WHOLESALE

EXPORT of munitions from the Port of New York. The Port of New

York was of course where the bulk of the transatlantic liners

docked. The relevant legislation was quickly put into place. They’d

just made it “legal”, by a thread, but it was still better, certainly at

this stage, if this rather thin veneer wasn’t subjected to too much

public scrutiny. Strictly speaking of course, the cargoes WERE

contraband, because munitions ARE explosive. Once again, the

demonstration before the MEC, and the outcome of it, was

thoroughly reported in the New York Times.

The British Government placed their munitions import orders with

the Admiralty’s Trade Division, who in turn placed the orders with

American businessman J Pierpoint Morgan, owner of the

International Mercantile Marine Company. Morgan was officially

appointed as sole purchaser for the British Government’s munitions

requirements in January of 1915 and he worked as such on the

basis of his receiving a 1% commission of all order values.

Morgan in turn, used a complex chain of fictitious companies to

secure the necessary items. The IMM’s ships and passengers then

became the unwitting carriers of this contraband, assisted by any

ships the British Admiralty had any control over or could otherwise

charter. In order to get the vital munitions aboard the chosen

passenger ships, it became standard practice to file a less than

truthful manifest with the US Collector of Customs in the Port of

New York. This manifest would show a purely general cargo. Later,

once each ship had left US territorial waters, a “Supplemental

Manifest” would be filed with the Customs office, listing any “last

minute provisions or cargo items” that had been loaded, though the

nature of any obviously suspect consignments would be slightly

altered or otherwise listed.

But what if the Collector of Customs found out?

A far better question is:

What if the Collector of Customs was in on it in the first place?

But why on Earth would the US Collector of Customs acquiesce in

such a practice? To issue a ship with a sailing clearance certificate,

which is after all a legal document, knowing it was based on a less

than truthful manifest, was surely a criminal offence? Are we talking

Bribery? Corruption? Ignorance? Or even just a conspiracy theory?

If it were true, that this Customs Official knew what was going on

and that he willingly took a part in it, surely he’d have ended up in

prison sooner or later?

So, who was the US Collector of Customs for the Port of New York

in 1915?

That man was Dudley Field Malone.

An active member of the Democrat Party, Dudley Malone was the

son of a Philadelphia Democratic Official; William C. Malone and

Rose (McKenny) Malone. He was born on June 3rd 1882.

Malone was put in the office of Collector of Customs for the Port of

New York by President Woodrow Wilson in 1913, though Wilson

needed the backing of his friend, New York Senator James A O'

Gorman, to secure Malone’s appointment. O' Gorman was very

much the rising star in the New York Democrat camp at that time.

He was already on NYC's Legislature Committee and with his

appointment to the Foreign Relations Committee in 1913 O’

Gorman’s influence, especially in New York, was assured. Senator

O' Gorman readily consented to Wilson’s wish, mainly because

Dudley Malone had been married to his daughter, May O’ Gorman,

for five years at the time.

Malone was a Lawyer by trade, specialising in Divorce and

Probate. He was also very much a personal friend and political ally

of President Wilson's. Both Wilson and Malone often spoke publicly

and in the press, in support of each other. Malone went on the

campaign trail with Wilson for the President's 1916 re-election

campaign. Being O'Gorman's son-in-law would undoubtedly have

been beneficial on the campaign trail too.

Malone however, had a lot of political and financial skeletons

rattling around in his closet: Skeletons that had a nasty habit of

exposing themselves every now and again. Skeletons such as his

being under official investigation for aspects of his estate lawyering

activities, in March of 1916. Malone had stood accused of

fraudulently hiding assets, possessing dubious "gifts" and other

financial irregularities. This was to be a recurrent theme in his life.

After Wilson's re-election, Malone resigned as Collector of Customs

due to a political disagreement with Wilson over the women's

movement, being succeeded as Collector by Byron P Newton in

October of 1917. Malone then announced his public support for the

Socialist Morris Hillquit, in his quest to become Mayor of NYC.

Malone himself was being publicly attacked in the press at that time

by members of the Roman Catholic Church in Brooklyn, over his

politics. Malone’s own arrogance seems to have prevented him

from realising that he was becoming something of a liability to the

Democrats by then.

By 1918 however, he was back in the Democrat fold again, fighting

the feminist cause in support of Wilson; but not for long. In 1920 he

ran for Governor of New York on the Farmer-Labour Party ticket,

earning just 69,908 votes versus 1,335,617 votes for winning

Republican Nathan L. Miller, 1,261,729 for incumbent Democrat Al

Smith and 171,907 for the Socialist Joseph Cannon. After this

ignominious defeat, Malone left the Democrats to become an

Independent.

In 1921, his wife May O' Gorman, divorced him, and he took

another wife, the feminist and writer Doris Stevens. They moved to

Paris, France, where he'd recently set up a Law firm. However, he

was soon back home in the States and being sued for malpractice

by one or two of his French clients. In 1929, his second wife also

divorced him. He spent most of the early thirties flitting backwards

and forwards between the US and France whilst still being pursued

by at least three of his more notable clients over money. He then

married Edna L. Johnson in a London Registry Office in January of

1930. In 1931, he and his third wife went on a cruise to Bermuda,

probably to escape the ever growing number of his clients who

were hounding him over money. By 1935, he had filed for

bankruptcy, owing more than $260,000, though he managed to

wriggle out of one of the law suits against him.

In 1943, he played the part of his old friend, WINSTON

CHURCHILL, in a propaganda film called Mission to Moscow.

In 1949, he was beaten up at the roadside by two men, which

hardly seems surprising at all. He died at Culver City Hospital,

California, in 1950. Ever the social-climber, Dudley Malone seems

to have been rather a shady character, to say the least.

So, to return to the question of “What if the US Collector of

Customs was in on it in the first place?”

Malone knew exactly what was taking place, but he was instructed

to turn a blind eye to the practice. Malone would issue a sailing

clearance certificate for each ship, usually the day before its

scheduled departure, based only on what was called a “Loading

Manifest”. Something like the real manifest, the “Supplemental

Manifest”, would be filed about three days after each ship had

sailed, when it was too late to do anything about it anyway.

During the outcry over the Lusitania case, Malone was asked by a

reporter from the New York Times, in his position as Collector of

Customs, if projectiles such as those used by the Artillery could be

classed as explosives. He was quoted in the paper as stating that:

“If no fuse was fitted to them then they would be classified as being

NON-EXPLOSIVE. Therefore any such projectiles as might be

loaded aboard a passenger ship would not be illegal under US law,

as long as it appeared on the manifest”. In short, he’d been treating

artillery shells as being nothing more than “big bullets” and bullets

were what the Municipal Explosives Committee of NYC had initially

sanctioned. If the fuse wasn’t fitted to it, then the shell, in theory,

had no means of detonation. Kapitan-Leutnant Schwieger of course

changed that, on Friday 7th May, 1915, by inadvertently introducing

a G6 torpedo amongst 5,000 of these supposedly NON-

EXPLOSIVE “big bullets”.

With his good friend Senator James A O' Gorman on New York

City's Legislature Committee it was obviously made much easier for

President Wilson to go a step further and get these now

miraculously “empty”/NON-EXPLOSIVE” munitions made legal to

transport on transatlantic passenger ships. Of course, Wilson also

had another personal friend, O' Gorman's son-in-law, Dudley

Malone, whom he’d personally put at the Head of Customs in New

York, who could then "legally" clear these munitions to be loaded

onto eastbound passenger ships. Given Malone’s background, then

and since, it would indeed seem highly likely that the wilful and

knowing issuing of sailing clearances on the basis of a less than

truthful manifest, would not have been beyond Dudley Malone at

all.

One week after the Lusitania disaster, The International Mercantile

Marine Company announced in the New York Times that “in future,

IMM ships would no longer carry munitions of war as cargo”. The

words in future and no longer should be particularly noted! Despite

this most public statement, liners of the White Star Line, (who were

owned by IMM), continued to sail from New York with vast

quantities of war materials in their holds. Their departures and the

nature of their cargoes were regularly published in the New York

Times. On December 10th, 1915, seven months after the Lusitania

was sunk, the New York Times announced that the White Star Liner

Adriatic had left New York carrying 18,000 tons of war munitions for

the Allies. Among the cargo items listed were 5,973 “empty” shells

(NON EXPLOSIVE of course). The ship’s total cargo was valued at

$10,000,000. Less than a year later, in August of 1916, the New

York Times again reported the sailing of another White Star Liner,

one of Adriatic’s sisters, the Baltic, carrying 18,500 tons of war

munitions for the Allies. Such reports were usually printed about

three days after the ship had left, once their supplemental

manifests had been filed with Malone’s office. That

gives an idea of the scale of the munitions shipping operation:

TWENTY MILLION DOLLARS worth of munitions exports, on just

those two ships alone, on ONE voyage. It is also worth noting that

the Adriatic and the Baltic were both about one third smaller than

the Lusitania.

Another interesting sub-point is that Charles M Schwab, President

of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, who manufactured most of the

munitions that were being shipped to Britain on these liners, was

himself a regular passenger on both the Lusitania and the

Mauretania.In the wake of the Lusitania disaster, “Champagne

Charlie” as he was known, was asked by the New York Times if it

was normal for his munitions products to leave the factory in crates

marked NON EXPLOSIVE. He stated that he had no idea, as he

wasn’t often there.In fact, he said; in the week that the Lusitania

had been sunk, he’d been away, so he felt he couldn’t possibly

comment on the matter further anyway.

By the end of 1915, the year in which the Lusitania was sunk,

exports of American-made munitions to Great Britain had totalled

$199, 627, 324. The monthly average for munitions exports during

the period 1st Jan 1915 to 1st Jan 1916 was $74, 003, 583. Both of

these figures were proudly announced in the business pages of the

New York Times of September 7th 1916. By the time of the US

entry into World War 1 in 1917, it had well and truly passed the

$1bn mark. All of it of course, had been sent by ship, and not just

from the port of New York. There were shipments from Boston and

Philadelphia too. We’ll leave you to work out what commission J P

Morgan had earned for himself as sole purchasing agent, at 1% of

all orders !