Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com

U20 and Kapitan-Leutnant Walther Schwieger.

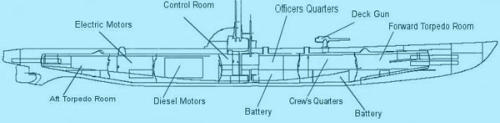

The U20 was built in the Danzig Dockyard in 1913. She was 210 feet long, just 20 feet in the beam and her surface displacement

was 650 tons . Submerged, her displacement was 837 tons.

She was propelled on the surface by two 850 horsepower Diesel engines. Whilst submerged, two 600 horsepower electric motors

took over the job of driving her twin screws.

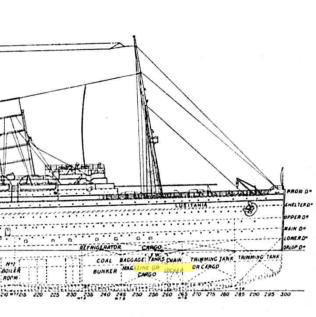

Deck Plans for U20

BundersArchiv/MilitarArchiv

Her armament consisted of four 19.7 inch torpedo tubes, two in the bow and two in the stern, plus one 4.1 inch deck gun. She

carried a stock of six torpedoes on each patrol.

U 20 was modified several times between 1913 and 1916. Her forward tubes were replaced with larger ones to accommodate the

latest G-type torpedoes, which necessitated the re-profiling of her original perpendicular bow, as seen on the original 1913/14

schematic drawing, to the rounded type shown on the blueprint above, which she closely resembled after the modifications were

finished.By the time U 20 was destroyed, she'd also had a ventilation shaft added, just forward of the conning tower, a feature also

shown on the 1917 blueprint above. At the time of her loss, U 20's form was pretty much that of the boat shown in the blueprint

image above. By the end of 1916, the general layout and specifications for a German U-boat were as those in the blueprint.

This is because the Germans had an excellent design in the "Germania" type boats originally developed by Krupp's, so they stuck

with it. Apart from size, armament and application, ocean-going German U-boats deviated little from this basic design pattern

throughout the Great War.

Born on 7th April 1885 to a noble family in Berlin, Walther von

Schwieger (he personally disliked the "von" and refrained from

using it) entered the Kaiserliche Marine as a Sea Cadet in

1903, at the age of 18 .

His initial training took place at the shore-based training

establishment Stosch and on 15th April, 1904 he was promoted

to the rank of Fahnrich zur See, which was generally speaking,

the Kaiserliche Marine's equivalent of the Royal Navy's

Midshipman.

In 1905, he was sent on a special course at the Marineschule and upon

his successful completion of the course, he was posted to a Naval Reserve vessel, the liner

Braunschweig.

Torpedo division intake 1906 (Fahnrich zur see Schwieger bottom right)

collection of Greg & Mary Hitt

Kapitan-Leutnant Walther Schwieger

drawing, by John Gray.

He was posted to the Kaiserliche Marine's Torpedo Division in 1906 and in September of that year he was commissioned as a

Leutenant zur see after which he served two years as a watch officer on torpedo boats, first the S105 and then G110.

On November 10th, 1908 he was promoted to the rank of Oberleutnant zur See and transferred to the light cruiser SMS Stettin.

In 1911, he transferred from SMS Stettin to the U-Boote Waffe (U-boat arm).

After serving as a Flaggleutnant on U14, Schwieger was promoted to the rank of Kapitan-Leutnant on September 19th, 1914. He

took command of U20 at the end of December that year and soon proved to be a popular commander. At the time he infamously

sank the Lusitania on May 7th 1915, Schwieger was 30 years old.

After the storm of protest caused by the Lusitania disaster, the Kaiser called a halt to unrestricted submarine warfare. This caused

a temporary lull in sinkings, though Schwieger and U-20 managed to sink the defensively armed White Star liner Cymric during

this period. Unbeknownst to Schwieger, the liner was carrying the body of one of the Lusitania victims home to America at the time.

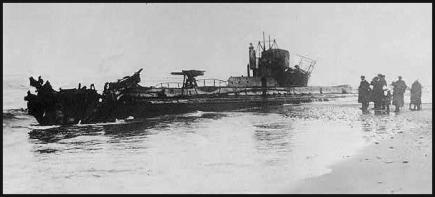

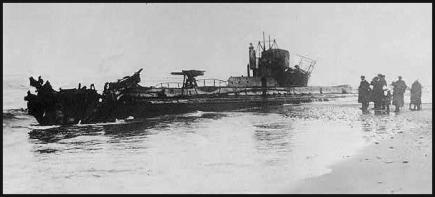

On November 5th, 1916 whilst trying to assist another U-boat, the U20 ran aground in fog off the Danish coast.She resisted all

attempts to refloat her and during the attempt to rescue Schwieger and his crew, the German Battleship KronPrinz Wilhelm, which

was providing protective screening for the rescue operation, was torpedoed by the British submarine J1.

The stranded U20 was therefore hastily blown up using one of her own torpedoes, to prevent her from falling into enemy hands.

The wreck of the U-20 off Denmark, seen here after Schwieger's

hasty attempt to blow her up. Library of Congress.

George Bain collection

KronPrinz Wilhelm limped back to base, only to end her days at the bottom of Scapa Flow, in Scotland, when the interned German

warships scuttled themselves in a last great act of defiance in 1919.

The Danish government eventually removed the wreck of U20 some years later, as she was a hazard to navigation. The remains

of U-20 are now a static display in Denmark, open to the public.

After U20 was lost, Schwieger was given command of the slightly larger U88 on April 7th, 1917 and on 30th July 1917, he was

awarded Germany's highest decoration for gallantry; the "Pour Le Merite" medal, or "Blue Max" as it was more popularly known,

in recognition of his having sunk a total of 190,000 tons of allied shipping. He was the 8th U-boat commander to receive this

covetted award. The citation for his award did not mention his largest victim; the Lusitania.

Schwieger was killed in action six weeks later, on September 5th 1917. Whilst being pursued by the Q-Ship HMS Stonecrop, the

submerged U88 struck a British laid mine off the Frisian island of Terschelling in the North Sea.

The British were quick to credit HMS Stonecrop with this "kill" as it made for good propaganda, but the mine that proved fatal to

Schwieger was not laid by HMS Stonecrop at all, and she certainly had not fired upon U-88 with any effect during the chase.

Walther Schwieger was seven months short of his 33rd birthday when his worst nightmare became a reality. here were no

survivors from the U88, whose last recorded resting place is 53,57N - 04,55E. At the time of his death, Schwieger ranked 6th in

the league table of top-scoring U-boat commanders and was therefore officially a U-boat "Ace".

In May of 1918, the first boat of "Project 46" was launched. Project 46 was a class of U-Cruiser and the very first was U139, which

was named "Kapitan-Leutnant Schwieger" in honour of his memory.

Between 1924 and 1925, parts of U20's wreck were recovered and put on display in several locations around the world. The

conning tower is today on display at Strandingsmuseum St. George, at Thorsminde, Denmark, as are one of U20's propellers and

her deck gun. Thorsminde is just a little south of Vrist, which is where U20 stranded. The remainder of U20's hull, including her

motors, still rests in the shallow water where she stranded, at 563500 N, 081000 E.

-------------

Many thanks to Mr Sondergaard who has emailed us about an auction that took place at Christie's, South Kensington, London on

Thursday, 14 May 1998.

In his own words he says

"On page 23 of the Christie's catalogue you will find a description af lot # 62 U-Boat 20 Bell, the submarine responsible for the

torpedoing of R.M.S Lusitania". There is a large picture of the bell on the same page. Further there is an account of the bell's

provenance.

It was I who acquired the bell at an auction in Denmark in 1975 for a rather modest sum. In 1998 I decided to sell it ( I always felt

that it was rather "spooky").At the same auction a large display model of the Cunard liner Lusitania (lot # 271) was also sold.

Both lots fetched the same price. "

Full range of the torpedo strike area projected by Ralf Bartzke's computer

simulation. Given that the relevant witness statements all put the impact BEHIND

the mast, and that there were no survivors from the Baggage Room, the range is

effectively narrowed to being from frame 247 to frame 257.

Lusitania Online.

Results of the Computer Simulation of U20’s attack on the Lusitania.

(Simulation performed by Herr Ralf Bartzke in Germany, with additional

information kindly supplied by Tom at www.uboataces.com).

Ralf Bartzke is a highly accomplished student of U-Boat tactics in Germany, who spent a long time researching U20’s attack on the

Lusitania in order to put all the necessary data into a specially designed computer simulator. The essential attack data was taken

from Schwieger’s War Diary and supplemented with other known torpedo data and U-Boat operational procedures for that time. What

follows now is the culmination of that research, plus the simulated attack.

When Schwieger planned his opportunist attack on the passing Lusitania, it was, of necessity, a case of rapid response planning.

He hadn’t time to thoroughly study her movements, as he would perhaps have wanted to.Once U20’s pilot, Lanz, had positively

identified the target as being one of the two Cunard sisters, Schwieger knew that his target was capable of at least 26 knots, that was

no secret, but his experienced eye told him that she was not moving as fast as that.

The first stage of the attack planning involved the systematic assimilation of the information gleaned about the intended target (in this

case, by Schwieger) at the attack periscope. This system was called UZO (U-Boot Ziel Optik or U-boat targeting, optics). As

Schwieger peered into the precision optics of his attack periscope, he had to estimate the target's speed then work out her heading,

distance, and bearing to the U-boat's bow. He estimated her speed as being 22 knots, which was an educated guess on his part.

Target speed was usually down to an inspired estimate, but again, data such as that gleaned by positive target identification could

help enormously. Then he saw her change course, noting in the boat’s War Diary that “the ship turns to starboard and takes a

course to Queenstown.” By following his coded wireless instructions from Vice-Admiral Coke, to divert Lusitania into Queenstown,

Captain Turner was now unknowingly and unwittingly shortening the range between his ship and the lurking U20.

To be sure his torpedo found its mark on such a fast target, Schwieger planned to hit the ship in a fairly centralised location,

anywhere between her first and fourth funnels and preferably around the second funnel area. Various instruments aboard the

U-Boat were used to assist in this. There was a range finding device in the attack periscope itself, called a Stadimeter, which was

basically a split-prism range-finder. Using a double-image of the target ship, it gave a pretty accurate range calculation up to a

maximum range of 6,000 meters. (Though at the 6, meter extremity of its range, the stadimeter’s accuracy was subject to a 10% error

factor). If certain other geometric information such as a known masthead height or funnel height for the target could also be factored

in, even more accuracy could be obtained.

Fortunately for Schwieger, Lusitania’s specifications were well known, thanks to the wealth of material that had been published

about her since her completion, particularly publications such as The Shipbuilder. (For example, Lusitania’s masthead was 165 feet

above her waterline). Contrary to popular belief, there was no cross-wire type of target sight in a U Boat’s periscope.

On the outside of the periscope’s control column was a Target Bearing Ring, which was usually read by an officer standing next to

whoever was using the periscope in the close confines of the base of the U-boat’s tower. The Target Bearing Ring gave the

compass bearing, measured in degrees, of the intended target in relation to the U-Boat’s bow.

All the UZO data was then manually processed using a slide rule and pre-determined tables to quickly calculate a firing solution. The

torpedoes travelled at different speeds, depths, and bearing to bow - all these factors were manually programmed into the torpedo

itself. When the torpedo was ready for firing, a light showed up for the loaded tube containing the now fully primed torpedo. The

final firing solution as predicted by Schwieger’s calculations is as follows:

Target’s speed estimated at 22 knots. Shot distance; 700 metres. G6 Torpedo, optimal speed; 35 knots = 18.01 m/s (meters per

second.) Torpedo running depth; 3 meters. Time to Target after firing= 700 meters @ 18.01 m/s = 38,9 seconds. Angle of intersection;

near 90 degrees.

Having run submerged at high speed, following the calculated firing plan, U20 arrived at the plan’s pre-disposed firing point. With

the boat’s speed then reduced, U20 was turned to port, into its firing position and the designated torpedo was fired. Schwieger then

relied on a stopwatch and further periscope observations to check the accuracy of his attack calculations.Ninety-seven years later,

with the same data fed into the simulator, Ralf’s computer simulation projected that the impact point would have been between

Lusitania’s second and third funnels, (around Frames 161-164) therefore amidships and pretty much where Schwieger was aiming to

hit her.

However, as Schwieger observed his torpedo hit the Lusitania through his periscope, the first thing he noticed was that the hit was

much further forward of where he planned. He immediately realised that he’d over-estimated the speed of the Lusitania. (The ship

was in fact making just 18 knots at the time, not his estimated 22).Then he saw and noted the almost immediate second, larger

explosion. He was at a loss to explain this, putting it down in his War Diary to possibly “Boilers, coal or powder?” Schwieger was

not to know that by a combination of chance and mis-calculation, his shot had in fact hit the ship in the one place that would render

fatal damage to her: the forward cargo hold. This is where the computer simulator Ralf used now truly comes into its own.

Target’s speed difference (estimated speed 22 knots - actual speed 18 knots=4 knot difference. 4 knots=2.06 meters per second.

Hit shift = 2.06 mps for 38.9 seconds = 80.1 meters = 262.5 feet FORWARD of the original projected impact point.

The control system of the G6 torpedo should have had a maximum rate of 1% possible deviation at a range of 700 metres. Maximum

possible deviation was thus 7 meters (23 feet). Allowing for this possible deviation in the calculation gives us a range of the hit being

the original 262.5 feet forward of the first simulated impact point +/- another possible 23 feet either way. Allowing for

this possible deviation gives a final range of the hit being between 239.5 to 285.5 feet further forward of the original computer

projected impact point. Those measurements, (allowing for the full scope of the possible 1% torpedo deviation) when transferred to

the ship’s deck plans, put the impact range anywhere between Frame 247 and possibly as far forward as, Frame 269. The mid-point

of this total range is between Frames 257 and 259. These frames are all located within the Lusitania’s cargo hold. Given that all

relevant witness statements put the torpedo’s impact behind the foremast, and that there were no survivors from Baggage Room,

(which was i immediately above the projected impact area) the range is effectively narrowed to being anywhere from Frame 247

forward to Frame 257, three meters below the waterline.

This computer simulation has thus confirmed the likelihood of the correctness of our original findings: that Schwieger’s torpedo did

indeed hit the ship in the aft end of her forward cargo hold, in the vicinity of her foremast (we originally said between frames 251

and 256) and certainly three meters below her waterline. It was also where 5,000 live artillery shells were stacked, in simple

unprotected wooden crates.

CHARLES VOEGELE: AN INTRIGUING STORY OF HUMANITY IN WAR?

Earlier in 2011, we were contacted by Mr Richard Heier in America who asked if we had any information about a relative of his,

who was supposed to have been a member of U20's crew; a seaman by the name of Charles Voegele. For reasons that will become

clear in a moment, I told him we didn’t, but put him in touch with the BundesMilitarArchiv in Germany whilst we searched elsewhere

on his behalf. We also posted two specific requests for information on Voegele on this website.

Anyone who has read books about the Lusitania disaster will have heard of Voegele. If the story about him is true, he apparently

refused Schwieger's order to fire the torpedo and after being shoved aside by Wiesbach (U20’s torpedo officer) he was placed

under arrest and subsequently court-martialled for his attack of humanity/cowardice, whichever way one chooses to view it.

The story of Charles Voegele was printed in Des Hickey and Gus Smith's book, SEVEN DAYS TO DISASTER. We discovered

however that the story was originally published in 1972 as an article by Prof. M A Ricklin of Strasbourg University, in the French

newspaper Le Monde. Presumably, Hickey and Smith got it from there. As we could find nothing to either prove or disprove the

story when we were writing THE LUSITANIA STORY, we simply left it out, but there was another author who, at a similar time, was

only too pleased to put this “human interest” story in their largely “humanist view of the disaster” work. What follows now is the latest

email we received from Richard Heier on the subject.

My mother’s oldest brother Jakob Voelker 1900-1987 was married twice. His first wife Lucy Birchler 1900-1952, descended from

Swiss immigrants which had settled in Fulda Indiana shortly after 1848. In 1956, the widower Jakob had visited Switzerland and while

there had married Gertrud (Trudy) Vögele 1918-2013. Having previously done the seven Birchler family charts, I had then interviewed

Trudy in 1983 about her family and transcribed all of her family data. One incident from that interview I still vividly recall, almost three

decades later, was the Christian name of one of her many nephews. She said his name was Charles Vögele 1923-2002 and I

challenged her, suggesting that in fact it was Karl and not the French form of that name. “No” she insisted, “It is Charles.” At the

time I wrote it down as such and that was the end of the story until late 2010. During that 1983 interview she had also mentioned that

Charles, a shoemaker by trade, had some years or decades earlier started a very successful shoe factory in Switzerland.

Forward to Fall 2010: I am scanning through all the donated books in the library of our condo association and discover one which

I had read, maybe a couple of years after it first appeared around 1983. It is ‘Seven Days to Disaster, The Sinking of the Lusitania’ by

Des Hickey & Gus Smith ISBN 0-399-12699-6. In it, it quotes the precise dialogue which supposedly transpired

when in 1915, Kapitan Schwieger of the German submarine U20, gave the order to ‘ready’ the torpedo, which was then fired at the

British passenger ship. Kapitan Schwieger had given the order to Charles Voegele to be then relayed by him to the torpedo officer

(Wiesbach). Voegele in turn, had refused to comply on moral grounds and had afterward been court martialled and then jailed in

Kiel until the end of the war in November of 1918. I noted the identical names of both my aunt’s nephew and that of the sailor but

mentally put these facts aside since I knew that Trudy’s nephew had been born in 1923, i.e. eight years after the sinking and thus

suspected no connection. Again time passed, but this time only a few months.

Wishing to keep my German speaking skill from withering away, I currently participate in two independent conversation groups in

downtown Milwaukee. The first group meets twice a month at Hefter Hall at the University of Wisconsin and the other once monthly at

the Cheese Mart on Third Street. During one of these meeting I had been given a copy of a then current German- American

publication “Neu Yorker Staats-Zeitung & German Times” which features an article about Charles Vögele Fashion Day in 2011. [305]

The main theme of the ad was the fact that Charles Vögele GmbH has recently signed on the German film star and producer Til

Schweiger *1963 as one of its several glamorous spokespeople. Apparently the once humble footware entrepreneur had

metamorphosed very successfully into a fashion clothing empire.

The fact that the almost identical surnames Schwieger and Schweiger are suddenly associated with the names of the two different

Charles Vögele finally arouses my curiosity. As a result I read ‘Lusitania, an Epic Tragedy’ by Diana Preston ISBN 0-8027-1375-0,

hoping to find a possible hint of a family connection between these two Charles Vögele. The specific bibliographies on the Voegele

names in both of these books are super sparse and found me contacting all the authors and publishers without getting their ear

even once. Hickey & Smith are probably dead and Diana Preston could not be approached, even via her publisher. Hickey & Smith

gave a brief credit for their Voegele data to a Professor M.A. Ricklin, but did not mention his full name, residence or academic

affiliation. Thus this reference material could not be re-examined for additional details such as the birth date, birthplace & burial site of

this supposed Alsatian sailor.

It was at about this point that Richard contacted us at Lusitania Online, asking for our help. We posted his request on our site and put

him onto the BundesMilitarArchiv first and we made some enquiries as well. He continues:

The background setting of both of these Charles Voegele is also most interesting. The Swiss line originated in Gerlingen, just a

couple kilometers NW of Stuttgart and migrated about 153 Km (95 miles) SE to Gossau, Switzerland in around 1870. The sailor

supposedly came from and was buried in Strasbourg, Alsace (Elsass, France) in either 1920 or 1926, depending upon which book

you are reading. All of these places are ancient Aleman territory [310], who have traditionally spoken the same German dialect, but

are currently trisected by the common borders between France, Germany and Switzerland, a situation somewhat similar to that of

northern and southern Ireland. Stuttgart and Strasbourg are only around 110 kilometers apart and the current 2011 rail travel time is 1

hour, 19 minutes.

What is even more intriguing is the fact that both literature and television broadcasts put precise defiant and treasonable quotes into

this supposed sailor’s mouth, yet not one single locatable document hints or supports the fact that he, as an actual person, ever

existed. The Sinking of the Lusitania: Terror at Sea was aired in England in 2007 & in Germany in 2008.

Even the German military archives [320] in Freiburg came up with nothing. As a result of this situation, the question arose: Is this

Charles Voegele an urban legend that has metamorphosed into literary fact, without anyone wishing to challenge it? Did Des Hickey

& Gus Smith fabricate the personage Voegele, and if so why? Somehow I found this scenario too difficult to accept.

If the sailor died indeed in 1920, then there is a fair possibility that his namesake, who was born 1923 in Switzerland, may have

been named after him. This likelihood however diminishes considerably, should it prove that the sailor died in 1926. My effort to re-

establish my previous 1983 contact with Switzerland, have so far failed. There is no response to any of my emails.

At about this time, we informed Richard that we’d found a record of Prof Ricklin’s article, which was titled LAST VICTIM OF THE

LUSITANIA. It had first appeared in the well-known French Newspaper Le Monde in 1972. At that point, we also furnished him with

the contact details for Le Monde. He continues:

By early December 2011 most of the dust settled. I had previously found the birth certificate of the sailor Charles Vögele 1886-1926

and then the University of Strasbourg records of M.A. Ricklin. Shortly thereafter the Marine Nachrichten Blatt [330] in Germany

had seen my query on the Lusitania.net website and asked me to share my data, which I readily did. They in turn then tediously

combed through all known military archives in Germany and found the previous ever elusive sailor Karl Vögele, later known as

Charles Voegele. Their findings on him were astounding. Yes, he had twice served as a sailor in the Imperial German Navy, but

records revealed that he had never served on a submarine nor had he ever been court martialled as claimed in ‘Seven Days to

Disaster, The Sinking of the Lusitania’.Meanwhile, an entirely separate enquiry about U20’s attack on the Lusitania was also about to

contribute to this event. Ralf Bartzke, a student of U Boat tactics in Germany had contacted us about the actual torpedoing of the

ship. During our exchanges, we mentioned the Voegele story. Ralf very kindly ran the attack through a computer simulator for us,

using two scenarios. One, the attack as we know it and the other introducing an estimated delay of 5 seconds in the firing of the

torpedo, caused by Voegele’s refusal and Wiesbach’s intervention. The simulator showed us that if the Voegele story were true,

the delayed torpedo would have hit the ship aft of her four funnels, which we know didn’t happen, because of clear evidence to the

contrary plus the undeniable fact that the ship sank bows first. We passed Ralf’s findings and the simulator data on to Richard, who

concludes:

The whole story has thus revealed itself to be a concoction by this Prof. M.A. Ricklin which he had initially published in 1972 in the

French newspaper Le Monde. This conclusion is further reinforced by all the facts now known about the U20’s personnel, command

procedure and tight physical structure within the small submarine.

The details of this expose will be published (in German only?) in January 2012 in the Marine Nachrichten Blatt, and be also

accessible via http://www.seekrieg14-18.de

The (captain) Schwieger and (film actor) Schweiger name similarities, which had triggered this search in the first place, were nothing

but a coincidence. I requested the university archivist in Strasbourg to continue searching for the supposed reference material used

by Ricklin for his article, but seriously doubt if this will be attempted, but if so, that anything of consequence will ever be found.

Unfortunately the published misinformation on the sailor Charles Voegele, via M.A. Ricklin in current French biographical references,

shall remain in circulation since it was previously published and will most likely never be retracted.

In summation, the final findings are that the two different Charles Voegele were not closely related and that the stories attributed to

the U20 sailor were a pure figment of Professor M.A. Ricklin’s imagination. Unfortunately several authors and television personalities

accepted Ricklin’s misinformation as gospel truth and incorporated it into their books and dramas. Wishing to help rectify this

situation, the Lusitania.net website then published these findings on this website early in December 2011.

In April of 2012, Bernd Langensiepen of the Marine Nachrichten Blatt obtained the relevant official crew list of U-20. It was found in

the "War Crime" documents from "Droescher" in the "BundesArchiv / MilitarAarchiv".

There is nobody by the name of C. Voegele listed as a crew member.

Now that the facts are known, the only remaining mystery is why this factious tale had ever created in the first place. What possible

purpose had been its creation and publication back in 1972? That we shall probably never know. Hopefully the old incorrect

biographically references of Voegele and Ricklin will over the decades just wither away as they should since they only brought and

still continue to bring shame to their creator.

I am currently in contact with a Ricklin here in the USA and because of his comments, suspect that he may be related to the

M.A.Ricklin who started this whole fiasco. We may think that this whole Charles Voegele story is finally all wrapped up, but I wish to

remain open minded on this subject. Hopefully we shall not be receiving any negative comments.

Please forward comments or independent findings to RFHeier@att.net

Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com

U20 and Kapitan-Leutnant Walther Schwieger.

The U20 was built in the Danzig Dockyard in 1913. She was 210

feet long, just 20 feet in the beam and her surface displacement

was 650 tons . Submerged, her displacement was 837 tons.

She was propelled on the surface by two 850 horsepower Diesel

engines. Whilst submerged, two 600 horsepower electric motors

took over the job of driving her twin screws.

Deck Plans for U20

BundersArchiv/MilitarArchiv

Her armament consisted of four 19.7 inch torpedo tubes, two in the

bow and two in the stern, plus one 4.1 inch deck gun. She carried a

stock of six torpedoes on each patrol.

U 20 was modified several times between 1913 and 1916. Her

forward tubes were replaced with larger ones to accommodate the

latest G-type torpedoes, which necessitated the re-profiling of her

original perpendicular bow, as seen on the original 1913/14

schematic drawing, to the rounded type shown on the blueprint

above, which she closely resembled after the modifications were

finished.By the time U 20 was destroyed, she'd also had a

ventilation shaft added, just forward of the conning tower, a feature

also shown on the 1917 blueprint above. At the time of her loss, U

20's form was pretty much that of the boat shown in the blueprint

image above. By the end of 1916, the general layout and

specifications for a German U-boat were as those in the blueprint.

This is because the Germans had an excellent design in the

"Germania" type boats originally developed by Krupp's, so they

stuck with it.

Apart from size, armament and application, ocean-going German

U-boats deviated little from this basic design pattern throughout the

Great War.

Kapitan-Leutnant Walther Schwieger drawing, by John Gray.

Born on 7th April 1885 to a noble family in Berlin, Walther von

Schwieger (he personally disliked the "von" and refrained from

using it) entered the Kaiserliche Marine as a Sea Cadet in 1903, at

the age of 18 .

His initial training took place at the shore-based training

establishment Stosch and on 15th April, 1904 he was promoted to

the rank of Fahnrich zur See, which was generally speaking, the

Kaiserliche Marine's equivalent of the Royal Navy's Midshipman.

In 1905, he was sent on a special course at the Marineschule and

upon his successful completion of the course, he was posted to a

Naval Reserve vessel, the liner Braunschweig.

Torpedo division intake 1906 (Fahnrich zur see Schwieger bottom

right)

collection of Greg & Mary Hitt

He was posted to the Kaiserliche Marine's Torpedo Division in 1906

and in September of that year he was commissioned as a

Leutenant zur see after which he served two years as a watch

officer on torpedo boats, first the S105 and then G110.

On November 10th, 1908 he was promoted to the rank of

Oberleutnant zur See and transferred to the light cruiser SMS

Stettin. In 1911, he transferred from SMS Stettin to the U-Boote

Waffe (U-boat arm).

After serving as a Flaggleutnant on U14, Schwieger was promoted

to the rank of Kapitan-Leutnant on September 19th, 1914. He took

command of U20 at the end of December that year and soon

proved to be a popular commander. At the time he infamously sank

the Lusitania on May 7th 1915, Schwieger was 30 years old.

After the storm of protest caused by the Lusitania disaster, the

Kaiser called a halt to unrestricted submarine warfare. This caused

a temporary lull in sinkings, though Schwieger and U-20 managed

to sink the defensively armed White Star liner Cymric during this

period. Unbeknownst to Schwieger, the liner was carrying the body

of one of the Lusitania victims home to America at the time.

On November 5th, 1916 whilst trying to assist another U-boat, the

U20 ran aground in fog off the Danish coast.She resisted all

attempts to refloat her and during the attempt to rescue Schwieger

and his crew, the German Battleship KronPrinz Wilhelm, which was

providing protective screening for the rescue operation, was

torpedoed by the British submarine J1.

The stranded U20 was therefore hastily blown up using one of her

own torpedoes, to prevent her from falling into enemy hands.

The wreck of the U-20 off Denmark, seen here after Schwieger's

hasty attempt to blow her up. Library of Congress.

George Bain collection

KronPrinz Wilhelm limped back to base, only to end her days at the

bottom of Scapa Flow, in Scotland, when the interned German

warships scuttled themselves in a last great act of defiance in 1919.

The Danish government eventually removed the wreck of U20

some years later, as she was a hazard to navigation. The remains

of U-20 are now a static display in Denmark, open to the public.

After U20 was lost, Schwieger was given command of the slightly

larger U88 on April 7th, 1917 and on 30th July 1917, he was

awarded Germany's highest decoration for gallantry; the "Pour Le

Merite" medal, or "Blue Max" as it was more popularly known, in

recognition of his having sunk a total of 190,000 tons of allied

shipping.

He was the 8th U-boat commander to receive this covetted award.

The citation for his award did not mention his largest victim; the

Lusitania.

Schwieger was killed in action six weeks later, on September 5th

1917. Whilst being pursued by the Q-Ship HMS Stonecrop, the

submerged U88 struck a British laid mine off the Frisian island of

Terschelling in the North Sea.

The British were quick to credit HMS Stonecrop with this "kill" as it

made for good propaganda, but the mine that proved fatal to

Schwieger was not laid by HMS Stonecrop at all, and she certainly

had not fired upon U-88 with any effect during the chase.

Walther Schwieger was seven months short of his 33rd birthday

when his worst nightmare became a reality. here were no survivors

from the U88, whose last recorded resting place is 53,57N -

04,55E. At the time of his death, Schwieger ranked 6th in the

league table of top-scoring U-boat commanders and was therefore

officially a U-boat "Ace".

In May of 1918, the first boat of "Project 46" was launched. Project

46 was a class of U-Cruiser and the very first was U139, which was

named "Kapitan-Leutnant Schwieger" in honour of his memory.

Between 1924 and 1925, parts of U20's wreck were recovered and

put on display in several locations around the world. The conning

tower is today on display at Strandingsmuseum St. George, at

Thorsminde, Denmark, as are one of U20's propellers and her deck

gun. Thorsminde is just a little south of Vrist, which is where U20

stranded. The remainder of U20's hull, including her motors, still

rests in the shallow water where she stranded, at 563500 N,

081000 E.

-------------

Many thanks to Mr Sondergaard who has emailed us about an

auction that took place at Christie's, South Kensington, London on

Thursday, 14 May 1998.

In his own words he says

"On page 23 of the Christie's catalogue you will find a description af

lot # 62 U-Boat 20 Bell, the submarine responsible for the

torpedoing of R.M.S Lusitania". There is a large picture of the bell

on the same page. Further there is an account of the bell's

provenance.

It was I who acquired the bell at an auction in Denmark in 1975 for

a rather modest sum. In 1998 I decided to sell it ( I always felt that it

was rather "spooky").At the same auction a large display model of

the Cunard liner Lusitania (lot # 271) was also sold. Both lots

fetched the same price. "

Results of the Computer Simulation of U20’s attack on the Lusitania

(Simulation performed by Herr Ralf Bartzke in Germany, with

additional information kindly supplied by Tom at

(www.uboataces.com).

Ralf Bartzke is a highly accomplished student of U-Boat tactics in

Germany, who spent a long time researching U20’s attack on the

Lusitania in order to put all the necessary data into a specially

designed computer simulator. The essential attack data was taken

from Schwieger’s War Diary and supplemented with other known

torpedo data and U-Boat operational procedures for that time. What

follows now is the culmination of that research, plus the simulated

attack.

When Schwieger planned his opportunist attack on the passing

Lusitania, it was, of necessity, a case of rapid response planning.

He hadn’t time to thoroughly study her movements, as he would

perhaps have wanted to.Once U20’s pilot, Lanz, had positively

identified the target as being one of the two Cunard sisters,

Schwieger knew that his target was capable of at least 26 knots,

that was no secret, but his experienced eye told him that she was

not moving as fast as that.

The first stage of the attack planning involved the systematic

assimilation of the information gleaned about the intended target

(in this case, by Schwieger) at the attack periscope. This system

was called UZO (U-Boot Ziel Optik or U-boat targeting, optics). As

Schwieger peered into the precision optics of his attack periscope,

he had to estimate the target's speed then work out her heading,

distance, and bearing to the U-boat's bow. He estimated her speed

as being 22 knots, which was an educated guess on his part.

Target speed was usually down to an inspired estimate, but again,

data such as that gleaned by positive target identification could help

enormously. Then he saw her change course, noting in the boat’s

War Diary that “the ship turns to starboard and takes a course

to Queenstown.” By following his coded wireless instructions from

Vice-Admiral Coke, to divert Lusitania into Queenstown, Captain

Turner was now unknowingly and unwittingly shortening the range

between his ship and the lurking U20.

To be sure his torpedo found its mark on such a fast target,

Schwieger planned to hit the ship in a fairly centralised location,

anywhere between her first and fourth funnels and preferably

around the second funnel area. Various instruments aboard the U-

Boat were used to assist in this.There was a range finding device in

the attack periscope itself, called a Stadimeter, which was basically

a split-prism range-finder. Using a double-image of the target ship,

it gave a pretty accurate range calculation up to a maximum range

of 6,000 meters. (Though at the 6, meter extremity of its range, the

stadimeter’s accuracy was subject to a 10% error factor). If certain

other geometric information such as a known masthead height or

funnel height for the target could also be factored in, even more

accuracy could be obtained.

Fortunately for Schwieger, Lusitania’s specifications were well

known, thanks to the wealth of material that had been published

about her since her completion, particularly publications such as

The Shipbuilder. (For example, Lusitania’s masthead was 165 feet

above her waterline). Contrary to popular belief, there was no

cross-wire type of target sight in a U Boat’s periscope.

On the outside of the periscope’s control column was a Target

Bearing Ring, which was usually read by an officer standing next to

whoever was using the periscope in the close confines of the base

of the U-boat’s tower. The Target Bearing Ring gave the compass

bearing, measured in degrees, of the intended target in relation to

the U-Boat’s bow.

All the UZO data was then manually processed using a slide rule

and pre-determined tables to quickly calculate a firing solution. The

torpedoes travelled at different speeds, depths, and bearing to bow

- all these factors were manually programmed into the torpedo

itself. When the torpedo was ready for firing, a light showed up for

the loaded tube containing the now fully primed torpedo. The final

firing solution as predicted by Schwieger’s calculations is as

follows:

Target’s speed estimated at 22 knots. Shot distance; 700 metres.

G6 Torpedo, optimal speed; 35 knots = 18.01 m/s (meters per

second.)

Torpedo running depth; 3 meters. Time to Target after firing= 700

meters @ 18.01 m/s = 38,9 seconds. Angle of intersection; near 90

degrees.

Having run submerged at high speed, following the calculated firing

plan, U20 arrived at the plan’s pre-disposed firing point. With the

boat’s speed then reduced, U20 was turned to port, into its firing

position and the designated torpedo was fired. Schwieger then

relied on a stopwatch and further periscope observations to check

the accuracy of his attack calculations.Ninety-seven years later,

with the same data fed into the simulator, Ralf’s computer

simulation projected that the impact point would have been

between Lusitania’s second and third funnels, (around Frames 161-

164) therefore amidships and pretty much where Schwieger was

aiming to hit her.

However, as Schwieger observed his torpedo hit the Lusitania

through his periscope, the first thing he noticed was that the hit was

much further forward of where he planned. He immediately realised

that he’d over-estimated the speed of the Lusitania. (The ship was

in fact making just 18 knots at the time, not his estimated 22).Then

he saw and noted the almost immediate second, larger explosion.

He was at a loss to explain this, putting it down in his War Diary to

possibly “Boilers, coal or powder?” Schwieger was not to know that

by a combination of chance and mis-calculation, his shot had in fact

hit the ship in the one place that would render fatal damage to her:

the forward cargo hold. This is where the computer simulator Ralf

used now truly comes into its own.

Target’s speed difference (estimated speed 22 knots - actual speed

18 knots=4 knot difference. 4 knots=2.06 meters per second. Hit

shift = 2.06 mps for 38.9 seconds = 80.1 meters = 262.5 feet

FORWARD of the original projected impact point.

The control system of the G6 torpedo should have had a maximum

rate of 1% possible deviation at a range of 700 metres. Maximum

possible deviation was thus 7 meters (23 feet). Allowing for this

possible deviation in the calculation gives us a range of the hit

being the original 262.5 feet forward of the first simulated impact

point +/- another possible 23 feet either way. Allowing for this

possible deviation gives a final range of the hit being between

239.5 to 285.5 feet further forward of the original computer

projected impact point. Those measurements, (allowing for the full

scope of the possible 1% torpedo deviation) when transferred to the

ship’s deck plans, put the impact range anywhere between Frame

247 and possibly as far forward as, Frame 269. The mid-point of

this total range is between Frames 257 and 259. These frames are

all located within the Lusitania’s cargo hold. Given that all relevant

witness statements put the torpedo’s impact behind the foremast,

and that there were no survivors from Baggage Room, (which was i

immediately above the projected impact area) the range is

effectively narrowed to being anywhere from Frame 247 forward to

Frame 257, three meters below the waterline.

This computer simulation has thus confirmed the likelihood of the

correctness of our original findings: that Schwieger’s torpedo did

indeed hit the ship in the aft end of her forward cargo hold, in the

vicinity of her foremast (we originally said between frames 251 and

256) and certainly three meters below her waterline. It was also

where 5,000 live artillery shells were stacked, in simple unprotected

wooden crates.

Full range of the torpedo strike area projected by Ralf Bartzke's

computer simulation. Given that the relevant witness statements all

put the impact BEHIND the mast, and that there were no survivors

from the Baggage Room, the range is effectively narrowed to being

from frame 247 to frame 257.

Lusitania Online.

CHARLES VOEGELE: AN INTRIGUING STORY OF HUMANITY IN

WAR?

Earlier in 2011, we were contacted by Mr Richard Heier in America

who asked if we had any information about a relative of his, who

was supposed to have been a member of U20's crew; a seaman by

the name of Charles Voegele. For reasons that will become clear in

a moment, I told him we didn’t, but put him in touch with the

BundesMilitarArchiv in Germany whilst we searched elsewhere on

his behalf. We also posted two specific requests for information on

Voegele on this website.

Anyone who has read books about the Lusitania disaster will have

heard of Voegele. If the story about him is true, he apparently

refused Schwieger's order to fire the torpedo and after being

shoved aside by Wiesbach (U20’s torpedo officer) he was placed

under arrest and subsequently court-martialled for his attack of

humanity/cowardice, whichever way one chooses to view it.

The story of Charles Voegele was printed in Des Hickey and Gus

Smith's book, SEVEN DAYS TO DISASTER. We discovered

however that the story was originally published in 1972 as an article

by Prof. M A Ricklin of Strasbourg University, in the French

newspaper Le Monde. Presumably, Hickey and Smith got it from

there. As we could find nothing to either prove or disprove the story

when we were writing THE LUSITANIA STORY, we simply left it out,

but there was another author who, at a similar time, was only too

pleased to put this “human interest” story in their largely “humanist

view of the disaster” work. What follows now is the latest email we

received from Richard Heier on the subject.

My mother’s oldest brother Jakob Voelker 1900-1987 was married

twice. His first wife Lucy Birchler 1900-1952, descended from Swiss

immigrants which had settled in Fulda Indiana shortly after 1848. In

1956, the widower Jakob had visited Switzerland and while there

had married Gertrud (Trudy) Vögele 1918-2013. Having previously

done the seven Birchler family charts, I had then interviewed Trudy

in 1983 about her family and transcribed all of her family data. One

incident from that interview I still vividly recall, almost three decades

later, was the Christian name of one of her many nephews. She

said his name was Charles Vögele 1923-2002 and I challenged her,

suggesting that in fact it was Karl and not the French form of that

name. “No” she insisted, “It is Charles.” At the time I wrote it down

as such and that was the end of the story until late 2010. During

that 1983 interview she had also mentioned that Charles, a

shoemaker by trade, had some years or decades earlier started a

very successful shoe factory in Switzerland.

Forward to Fall 2010: I am scanning through all the donated

books in the library of our condo association and discover one

which I had read, maybe a couple of years after it first appeared

around 1983. It is ‘Seven Days to Disaster, The Sinking of the

Lusitania’ by Des Hickey & Gus Smith ISBN 0-399-12699-6. In it, it

quotes the precise dialogue which supposedly transpired when in

1915, Kapitan Schwieger of the German submarine U20, gave the

order to ‘ready’ the torpedo, which was then fired at the British

passenger ship. Kapitan Schwieger had given the order to Charles

Voegele to be then relayed by him to the torpedo officer

(Wiesbach). Voegele in turn, had refused to comply on moral

grounds and had afterward been court martialled and then jailed in

Kiel until the end of the war in November of 1918. I noted the

identical names of both my aunt’s nephew and that of the sailor but

mentally put these facts aside since I knew that Trudy’s nephew

had been born in 1923, i.e. eight years after the sinking and thus

suspected no connection. Again time passed, but this time only a

few months.

Wishing to keep my German speaking skill from withering away, I

currently participate in two independent conversation groups in

downtown Milwaukee. The first group meets twice a month at

Hefter Hall at the University of Wisconsin and the other once

monthly at the Cheese Mart on Third Street. During one of these

meeting I had been given a copy of a then current German-

American publication “Neu Yorker Staats-Zeitung & German Times”

which features an article about Charles Vögele Fashion Day in

2011. [305] The main theme of the ad was the fact that Charles

Vögele GmbH has recently signed on the German film star and

producer Til Schweiger *1963 as one of its several glamorous

spokespeople. Apparently the once humble footware entrepreneur

had metamorphosed very successfully into a fashion clothing

empire.

The fact that the almost identical surnames Schwieger and

Schweiger are suddenly associated with the names of the two

different Charles Vögele finally arouses my curiosity. As a result I

read ‘Lusitania, an Epic Tragedy’ by Diana Preston ISBN 0-8027-

1375-0, hoping to find a possible hint of a family connection

between these two Charles Vögele. The specific bibliographies on

the Voegele names in both of these books are super sparse and

found me contacting all the authors and publishers without getting

their ear even once. Hickey & Smith are probably dead and Diana

Preston could not be approached, even via her publisher. Hickey &

Smith gave a brief credit for their Voegele data to a Professor M.A.

Ricklin, but did not mention his full name, residence or academic

affiliation. Thus this reference material could not be re-examined for

additional details such as the birth date, birthplace & burial site of

this supposed Alsatian sailor.

It was at about this point that Richard contacted us at Lusitania

Online, asking for our help. We posted his request on our site and

put him onto the BundesMilitarArchiv first and we made some

enquiries as well. He continues:

The background setting of both of these Charles Voegele is also

most interesting. The Swiss line originated in Gerlingen, just a

couple kilometers NW of Stuttgart and migrated about 153 Km (95

miles) SE to Gossau, Switzerland in around 1870. The sailor

supposedly came from and was buried in Strasbourg, Alsace

(Elsass, France) in either 1920 or 1926, depending upon which

book you are reading. All of these places are ancient Aleman

territory [310], who have traditionally spoken the same German

dialect, but are currently trisected by the common borders between

France, Germany and Switzerland, a situation somewhat similar to

that of northern and southern Ireland. Stuttgart and Strasbourg are

only around 110 kilometers apart and the current 2011 rail travel

time is 1 hour, 19 minutes.

What is even more intriguing is the fact that both literature and

television broadcasts put precise defiant and treasonable quotes

into this supposed sailor’s mouth, yet not one single locatable

document hints or supports the fact that he, as an actual person,

ever existed. The Sinking of the Lusitania: Terror at Sea was aired

in England in 2007 & in Germany in 2008.

Even the German military archives [320] in Freiburg came up with

nothing. As a result of this situation, the question arose: Is this

Charles Voegele an urban legend that has metamorphosed into

literary fact, without anyone wishing to challenge it? Did Des Hickey

& Gus Smith fabricate the personage Voegele, and if so why?

Somehow I found this scenario too difficult to accept.

If the sailor died indeed in 1920, then there is a fair possibility that

his namesake, who was born 1923 in Switzerland, may have been

named after him. This likelihood however diminishes considerably,

should it prove that the sailor died in 1926. My effort to re-establish

my previous 1983 contact with Switzerland, have so far failed.

There is no response to any of my emails.

At about this time, we informed Richard that we’d found a record of

Prof Ricklin’s article, which was titled LAST VICTIM OF THE

LUSITANIA. It had first appeared in the well-known French

Newspaper Le Monde in 1972. At that point, we also furnished him

with the contact details for Le Monde. He continues:

By early December 2011 most of the dust settled. I had previously

found the birth certificate of the sailor Charles Vögele 1886-1926

and then the University of Strasbourg records of M.A. Ricklin.

Shortly thereafter the Marine Nachrichten Blatt [330] in Germany

had seen my query on the Lusitania.net website and asked me to

share my data, which I readily did. They in turn then tediously

combed through all known military archives in Germany and found

the previous ever elusive sailor Karl Vögele, later known as Charles

Voegele. Their findings on him were astounding. Yes, he had twice

served as a sailor in the Imperial German Navy, but records

revealed that he had never served on a submarine nor had he ever

been court martialled as claimed in ‘Seven Days to Disaster, The

Sinking of the Lusitania’.Meanwhile, an entirely separate enquiry

about U20’s attack on the Lusitania was also about to contribute to

this event. Ralf Bartzke, a student of U Boat tactics in Germany had

contacted us about the actual torpedoing of the ship. During our

exchanges, we mentioned the Voegele story. Ralf very kindly ran

the attack through a computer simulator for us, using two

scenarios. One, the attack as we know it and the other introducing

an estimated delay of 5 seconds in the firing of the torpedo, caused

by Voegele’s refusal and Wiesbach’s intervention. The simulator

showed us that if the Voegele story were true, the delayed torpedo

would have hit the ship aft of her four funnels, which we know didn’t

happen, because of clear evidence to the contrary plus the

undeniable fact that the ship

sank bows first. We passed Ralf’s findings and the simulator data

on to Richard, who concludes:

The whole story has thus revealed itself to be a concoction by this

Prof. M.A. Ricklin which he had initially published in 1972 in the

French newspaper Le Monde. This conclusion is further reinforced

by all the facts now known about the U20’s personnel, command

procedure and tight physical structure within the small submarine.

The details of this expose will be published (in German only?) in

January 2012 in the Marine Nachrichten Blatt, and be also

accessible via http://www.seekrieg14-18.de

The (captain) Schwieger and (film actor) Schweiger name

similarities, which had triggered this search in the first place, were

nothing but a coincidence. I requested the university archivist in

Strasbourg to continue searching for the supposed reference

material used by Ricklin for his article, but seriously doubt if this will

be attempted, but if so, that anything of consequence will ever be

found. Unfortunately the published misinformation on the sailor

Charles Voegele, via M.A. Ricklin in current French biographical

references, shall remain in circulation since it was previously

published and will most likely never be retracted.

In summation, the final findings are that the two different Charles

Voegele were not closely related and that the stories attributed to

the U20 sailor were a pure figment of Professor M.A. Ricklin’s

imagination. Unfortunately several authors and television

personalities accepted Ricklin’s misinformation as gospel truth and

incorporated it into their books and dramas. Wishing to help rectify

this situation, the Lusitania.net website then published these

findings on this website early in December 2011.

In April of 2012, Bernd Langensiepen of the Marine Nachrichten

Blatt obtained the relevant official crew list of U-20. It was found in

the "War Crime" documents from "Droescher" in the "BundesArchiv

/ MilitarAarchiv".

There is nobody by the name of C. Voegele listed as a crew

member.

Now that the facts are known, the only remaining mystery is why

this factious tale had ever created in the first place. What possible

purpose had been its creation and publication back in 1972? That

we shall probably never know. Hopefully the old incorrect

biographically references of Voegele and Ricklin will over the

decades just wither away as they should since they only brought

and still continue to bring shame to their creator.

I am currently in contact with a Ricklin here in the USA and

because of his comments, suspect that he may be related to the

M.A.Ricklin who started this whole fiasco. We may think that this

whole Charles Voegele story is finally all wrapped up, but I wish to

remain open minded on this subject. Hopefully we shall not be

receiving any negative comments.

Please forward comments or independent findings to

RFHeier@att.net