Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com

The Sinking of R.M.S. Lusitania,

the rescue of survivors and the recovery of bodies.

Panic by John Gray

FLYING FISH seen here at the White Star pier in Queenstown.

She is on the extreme left of the picture, next to the jetty.

Captain Thomas Brierley, Master of the

FLYING FISH.

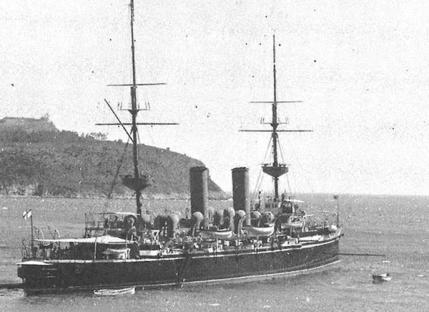

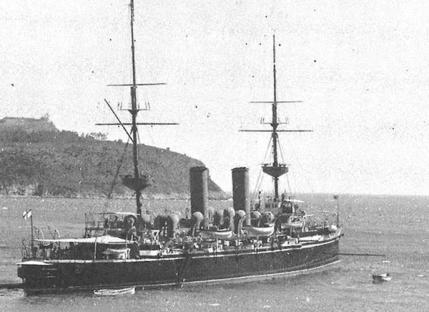

In this photo above, sailors from HMS Venus, an "Eclipse" class cruiser

belonging to the 11th Cruiser Squadron are helping to unload

recovered bodies from the rescue vessels in Queenstown. The sailors

are carrying the bodies to one of the many temporary mortuaries that

were set up in requisitioned buildings. Third from right is 17 year-old

Boy 1st Class Sailor Henry Grew temporarily attached to H.M.S.

Venus. (Lusitania Online)

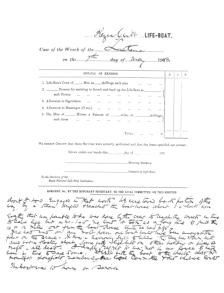

Clipping taken from the CORK EXAMINER.

HMS Venus, seen here in 1899 visiting the French port of Rouen.

(Musee de Maritime Rouen).

Henry Grew, photographed just after he was

promoted to Ordinary Seaman aboard HMS

Vanguard (David Grew/Lusitania Online).

A final "signal" to the then 48 year-old CPO Grew from Admiralty.

(David Grew/Lusitania Online)

The first section, Disaster, follows the events of "fateful Friday" from 11.00 in the morning to the time that the LUSITANIA sank

beneath the waves.

The second part, Rescue, has been written for the website using information and images supplied by Thomas Brierley, Great-

Grandson of the Captain Brierley mentioned in the text, to whom we are extremely grateful for this most personal of memories and

Dara Gannon, of the RNLI Lifeboat Station at Courtmacsherry, Ireland.

A third section, Recovery operation, has now been added thanks to information received from David Grew, the son of a late crew

member of the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Venus.

NOTE:

Any wireless instructions received by the LUSITANIA prior to 11.00 are not featured in the following excerpt but they are of course

fully dealt with in the books. What Captain Turner DIDN'T know at this point, was that the Admiralty in London had WITHDRAWN his

escort (without telling him) due to the KNOWN presence of a U-boat.

At this point in the story LUSITANIA was steering course South 87 East at 15 knots through thick fog, 25 miles off the south coast of

Ireland. Captain Turner was fully expecting to meet his naval escort, the light cruiser HMS Juno, at any time.

DISASTER

Friday 7th May 1915

At 11.00, the Lusitania broke through the fog into hazy sunshine. To port was an indistinct smudge, which was the Irish coastline.

But there was no sign of any other ships. No Juno.

Captain Turner increased the ship's speed to 18 knots. Barely had he done this when a messenger from the Marconi room brought

him a signal. It was 12 words, but he did not recognize the cypher. It was from Vice Admiral Coke in Queenstown.Because of the

high-grade code used to send the signal, he would have to take it down to his day cabin to work on it.

At 11.55 there was a knock on Turner's door. It was the messenger with another signal from the Admiralty; he broke off from his

decoding work to read it.

It said:

"SUBMARINE ACTIVE IN SOUTHERN PART OF IRISH CHANNEL,LAST HEARD OF TWENTY MILES SOUTH OF CONNINGBEG

LIGHT VESSEL.MAKE CERTAIN LUSITANIA GETS THIS."

This gave Captain Turner another problem. According to this latest message,another U-boat was operating in the very middle of the

channel he was aiming for.If this were true,then despite his Admiralty instructions,a mid channel course was now out of the question.

More than ever, he now had to determine his exact position, if he was going to have to play a potentially deadly game of cat and

mouse with a U-boat in a narrow channel entrance. But first he decided to finish deciphering Coke's earlier message.

By 12.10 he had finished decoding it completely. What he read galvanised him.He went straight to the bridge and immediately altered

the ship's course 20 degrees to port.The turn to port was so sudden that many passengers momentarily lost their balance. The

Lusitania was now closing to the land at 18 knots on course North 67 East. The clock on the bridge said 12.15, GMT. Atlantic Ocean,

22 miles off Waterford

The German submarine U-20 blew her tanks and surfaced. The fog, which had been troubling her commander, Kapitan-Leutnant

Walther Schwieger, had finally cleared.

They were now down to the last three torpedoes and his orders were to save two for the trip home,just in case they encountered an

enemy warship and had to fight their way out of it. Schwieger checked his watch. It was 12.20 GMT as the U-20 headed back toward

Fastnet at full speed.

At 12.40, whilst Lusitania was still on course N67E,Turner received another Admiralty signal.

This one read:

"SUBMARINE FIVE MILES SOUTH OF CAPE CLEAR, PROCEEDING WEST WHEN SIGHTED AT 10 AM."

He allowed himself a slight smile. Cape Clear was many miles astern of the eastbound Lusitania.

This latest signal effectively meant that the immediate danger was passed.The entrance to St. George's Channel and therefore the

next notified U-boat threat,would still be four to five hours away, if he had maintained his original heading.For now, he was safely in

the middle. As far as Captain Turner knew, there were NO U-boats in his immediate vicinity.

At 13.20 GMT, U-20 was still running on the surface, heading back toward Fastnet.Schwieger was up on the conning tower with the

lookouts. Suddenly, the starboard lookout saw smoke off the U-20s starboard bow. Schwieger focussed his binoculars on it. One, two,

three, four funnels.He estimated the distance between them to be 12 to 14 miles. It would be a long shot, but if the ship was heading

for Queenstown,it might just be possible.

As the diving klaxon screeched out it's warning.U-20 altered course to intercept the ship,submerging as she did so.

At 13.40 GMT, Captain Turner saw a landmark as familiar to him as his own front door. A Long promontory with a lighthouse on top of

it, which was painted with black and white horizontal bands. The Old head of Kinsale.

Now that he knew where he was, he ordered Lusitania's course reverted to South 87 East, steady. He urgently needed to fix his

position,in order to plot a course to Queenstown. They were not going to Liverpool after all, not yet anyway. The message from Vice

Admiral Coke which was sent in the high-grade naval code was ordering him to divert Lusitania into Queenstown immediately.

Standard Admiralty practice in situations of grave peril.

Turning back to his officers on the bridge,he noticed the ship's newest officer, whom he had christened Bisset (Junior Third Officer

Albert Bestic), due to go off watch in about 15 minutes. "Ah, Bisset. Do you know how to take a four point bearing?" he asked. Bestic

certainly did. He also knew that it took the best part of an hour with the ship's course and speed having to remain rock steady whilst it

was done. "Yes sir." He replied. "Good. Then kindly take one off that lighthouse, will you?"

And with that Turner left the bridge and went into the chartroom. Bestic needn't have worried. Lewis came back at 14.00 and relieved

him anyway, knowing what the "old man" had done.Bestic took the first set of bearing figures to Will in the chartroom on his way off

the bridge.

Captain Turner calculated that they were now 14 miles offshore and slightly West of the Old Head. He now had to plot a course

through the mine-free channel into Queenstown harbour.

Kapitan-Leutnant Walther Schwieger meanwhile, was studying the big ship through U-20's attack periscope. Calling to the U-boat's

pilot, Schwieger said,"four funnels, schooner rig, upwards of 20,000 tons and making about 22 knots." Lanz, the pilot, checked in his

copies of Jane's fighting ships and Brassey's naval annual. Lanz called back to Schwieger, "either the Lusitania or the Mauretania,

Herr Kapitan-Leutnant." (Both were listed in Brassey's as being armed merchant cruisers). "Both are listed as cruisers and used for

trooping."

U-20 prepared for action. One G6 torpedo was loaded into a forward tube. Schwieger then noticed the target altering course. He

could not believe his luck! He noted later in his logbook that "the ship turns to starboard then takes a course to Queenstown....."

Exactly what he had hoped she would do!

At a range of 650 yards, Schwieger gave the deadly order, "Feur!" There was a loud hiss, the U-boat trembled and Wiesbach,

the torpedo officer confirmed to Schwieger "Torpedo Los!" The G-Type torpedo had cleared the tube and was streaking toward its

intended target at 38 knots with its running depth set at three metres, about ten feet.

Meanwhile,

Captain Turner had come out of the chartroom and was standing on the port side of the Lusitania's bridge. He was watching Lewis

working on the four-point bearing.Beyond him, stood a Quartermaster right out on the bridge wing acting as a lookout.There was

another on the starboard bridge wing. But it was from the crows nest that the sudden warning came,via the telephone. "Torpedo

coming on the starboard side!" The torpedo struck the ship with a sound which Turner later recalled was "like a heavy door being

slammed shut." Almost instantaneously camea second, much larger explosion, which physically rocked the ship. A tall column of

water and debris shot skyward, wrecking lifeboat No. 5 as it came back down.The clock on the bridge said 14.10.

Watching events through his periscope, Kapitan-Leutnant Schwieger could not believe that so much havoc could have been wrought

by just one torpedo. He noted in his log that "an unusually heavy detonation" had taken place and noted that a second explosion had

also occurred which he put down to "boilers, coal or powder." He also noticed that the torpedo had hit the Lusitania further forward of

where he had aimed it. Schwieger brought the periscope down and U-20 headed back to sea.

On the bridge of the Lusitania, Captain Turner could see instantly that his ship was doomed. He gave the orders to abandon ship. He

then went out onto the port bridge wing and looked back along the boat deck. The first thing he saw was that all the port side lifeboats

had swung inboard, which meant that all those on the starboard side had swung outboard.The starboard ones could be launched,

though with a little difficulty, but the port side boats would be virtually impossible to launch.

Each of the wooden lifeboats weighed five tons unladen. To steady them, each had a metal chain called a snubbing chain which held

it to the deck.Prior to lowering the boat, the release pinhad to be knocked out using a hammer, otherwise the boat would remain

chained to the deck.

Beaching the ship was obviously out of the question. Turner knew they were fourteen miles from shore and she was sinking so fast

that they'd never make it. He had to stop the ship so that the boats could be safely lowered. Instinctively, he rang down to the engine

room for full speed astern.

The engine room dutifully complied but unfortunately, the overall steam pressure had now dropped drastically, so the Lusitania's

massive turbines were virtually out of commission.At 14.11, the Lusitania had started sending distress signals from the Marconi room.

"SOS, SOS, SOS. COME AT ONCE. BIG LIST. 10 MILES SOUTH OLD KINSALE. MFA."

The last three letters were the Lusitania's call sign.When Vice Admiral Coke in Queenstown received his copyof that distress signal,it

must have seemed as thoughhis worst nightmare had come true.

He had tried in vain all morning to obtaina firm decision from the Admiralty in London. In the end, Coke had been so worried by the

obvious danger that he had taken it upon himself to divert the Lusitania into Queenstown. Unfortunately, it was all too late.Still, there

was something he could do. He sent a signal to Rear Admiral Hood in command of HMS Juno and sent him to the rescue. Coke then

sent a detailed signal to the Admiralty, advising them of what had happened and of his actions. On the Lusitania, the list indicator had

just gone through the 15 degree mark.

Captain Turner was still out on the port side wing of the bridge. He had ordered Staff Captain Anderson not to lower any of the boats

until the ship had lost a sufficient amount of her momentum to render it safe.In some cases, on the port side, that meant getting the

passengers out of the lifeboats in order to lower them to the rail. But the passengers did not want to get out of the boats.

At port side boat station no.2, junior Third Officer Bestic was in charge. Standing on the after davit, he was trying to keep order and

explain that due to the heavy list, the boat could not be lowered. Suddenly, he heard the sound of a hammer striking the link-pin to the

snubbing chain. Before the word "NO!" left his lips, the chain was freed and the five-ton lifeboat laden with over 50 passengers,swung

inboard and crushed those standing on the boat deck against the superstructure.

Unable to take the strain, the men at the davits let go of the falls and boat 2, plus the collapsible boat stowed behind it,slid down the

deck towing a grisly collection of injured passengers and jammed under the bridge wing, right beneath the spot where Captain Turner

was.

Bestic, determined to stop the same situation arising at the next boat station, jumped along to no.4 boat; just as somebody knocked

out it's linkpin. He darted out of the way as no.4 boat slid down the deck maiming and killing countless more people, before crashing

into the wreckage of the first two boats.Driven by panic, passengers swarmed into boats 6, 8, 10 and 12. One after the other they

careered down the deck to join 2 and 4.

The sea was now swirling over the bridge floor. Then Lusitania's stern began to settle back and a surge of water flooded the bridge,

sweeping Captain Turner out of the door and off the ship.

As the Lusitania sank beneath the waves, that same surge of water swept junior Third Officer Bestic out through the first class

entrance hall into the Ocean.

The Lusitania was gone, and with her had gone 1, 201 people. It was now 14.28 GMT, on Friday 7th May, 1915.

REMINDER: You may wish to return to the page about Captain Turner at this point, if you entered this page from there.

RESCUE.

At approx. 2.30pm, intelligence was received by Rev William Forde; the then Hon Secretary of the Courtmacsherry Lifeboat Station,

that a large four funnel steamer was in distress South East of the Seven Heads. Rev Forde immediately went to summon the

volunteer lifeboat crew. On his arrival at the Lifeboat Station, then located at Barry’s Point he was met by the Coxswain and his crew.

At 3pm, the Courtmacsherry Lifeboat, Ketzia Gwilt under the command of Coxswain Timothy Keohane (Father of Antarctic explorer

Patrick Keohane) was launched. In calm conditions, the sails were of no use so the entire distance of approx. 12.6 nautical miles to

the casualty had to be rowed.

Almost identical lifeboat to the one sent out to the Lusitania from Courtmacsherry.

Photo; Dara Gannon, RNLI.

An extract from the original Courtmacsherry Return to Service log states “We had no wind, so had to pull the whole distance – On the

way to wreck we met a ship’s boat cramped with people who informed us the Lusitania had gone down. We did everything in our

power to reach the place but it took us at least 3 ½ hours of hard pulling to get there – then only in time to pick up dead bodies”. The

Courtmacsherry Lifeboat then proceeded in picking up as many bodies as they could and transferred them to the ships on scene

tasked with transferring bodies back to Queenstown.

Copy of Courtmacsherry Lifeboat Station Log for 7th May 1915. Photo: Dara Gannon, RNLI.

The final entry from the return to service log written by Rev Forde, who also joined the crew that day, reads: “Everything that was

possible to do was done by the crew to reach the wreck in time to save life but as we had no wind it took us a long time to pull the 10

or 12 miles out from the boat house. If we had wind or any motor power our boat would have been certainly first on the scene – It was

a harrowing sight to witness – The Sea was strewn with dead bodies floating about, some with lifebelts on others holding on pieces of

rafts – all dead. I deeply regret it was not in our power to have been in time to save some”.

Courtmacsherry Lifeboat stayed on scene engaged in the work of recovering bodies, until 20.40Hrs when they were then towed back

to the entrance of Courtmacsherry bay by a Steam Drifter fishing vessel. They partly rowed and partly sailed back the rest of

homeward journey, reaching the boat house at approx. 01.00Hrs on 8th May.

Meanwhile the Wanderer, a little fishing boat from the Isle of Man, was among the first to reach the scene and they picked up about

200 survivors. Although they were in danger of sinking with the overload, they still managed to take two of the Lusitania's lifeboats in

tow.

The Wanderer was intercepted about two miles of the Old Head of Kinsale by the Admiralty tug the Flying Fish, under the command

of Captain Thomas Brierley. The survivors were transferred to the tug and taken to Queenstown (Cobh), under Admiralty orders.

Captain Brierley and the Flying Fish made several such trips, gathering and ferrying survivors from the scene to Queenstown, and

many of those survivors owed their lives to him and his vessel. Most of the rescue ships were sailing vessels of the local fishing fleet

and would have taken hours in the light winds prevailing that day to reach the scene of the disaster, 12 miles offshore.The Flying Fish

was an old side-wheel paddle steamer built in 1886 at South Shields. Although just 122 feet long, and affectionately known amongst

the locals in Queenstown as the "Galloping Goose", she rendered a service that day which far outshone her diminutive size. As well

as serving as a tug, she was also used as a tender from the White Star Line pier at Queenstown, taking passengers and mail out to

the waiting liners.Captain Thomas Brierley was born in 1859, not 1861 as shown in the image above and was 56 at the time of the

disaster. He was awarded a medal for the outstanding gallantry he displayed during the endless trips he and his vessel made back

and forth from Queenstown, to where the Lusitania had sunk. Bringing back the living, as well as the dead. What must have been

particularly frustrating to this gallant mariner, was the fact that having heard of the disaster that had overtaken the Lusitania, he had to

wait, champing at the bit, for over an hour, for Flying Fish to build up steam before they could head out to the scene, knowing all the

while that lives were being lost all that time.

Even after overcoming that obstacle, Captain Brierley found himself caught up in red tape later when he tried to land survivors at a

pier not normally used by his vessel. He was kept waiting for "official permission" to dock, for what must have seemed like an eternity

to him, when his only concern was to safely offload his human cargo as quickly as possible so that he could return to the scene and

save more lives.

Captain Brierley died in 1920, aged just 61. He was buried in the same area as many of the victims of the Lusitania disaster. Victims

that he personally had tried so hard to save from the jaws of death.

The Recovery Operation.

On the afternoon of the disaster, the crews of the Royal Navy cruisers that were based in Queenstown were put to work tending to the

injured survivors and helping with the dead. The day after the disaster, the Bluejackets were sent out aboard the Admiralty tugs

Stormcock, Warrior and Flying Fish to recover bodies. Henry Grew was among those sent to perform this grisly task. The bodies were

brought back to Queenstown for subsequent burial in the mass graves that had been dug in the old church cemetery.

Henry Grew also recovered the cushion seen here, which was floating amid some bodies.

He dried it out and kept it, eventually passing it on to his son, David. David very kindly

passed it on to Lusitania Online in September 2003, for preservation. As for the man who

recovered the cushion, Henry Grew turned out to have the luck of the Devil. On 27th May

1915, he returned to his own ship the 19,250-ton "St Vincent" class Battleship HMS

Vanguard. He was with HMS Vanguard when the ship fought at Jutland and both Henry

and the ship came through the battle unscathed.

Thanks to our good friend Peter Boyd-Smith of "Cobwebs", we now know that the cushion came from a sofa in the First Class Music

Room, located within the First Class Lounge on the Lusitania's Boat Deck between funnels 3 and 4. On 1st November 2003, Lusitania

Online duly presented the cushion to the Merseyside Maritime Museum for permanent display.

She was thereafter thought to be a "lucky ship" and certainly Henry's former shipmates must have envied him his posting. On the

morning of July 9th 1917, after serving for a little over two years on HMS Vanguard, Henry was routinely posted to HMS Pembroke.

He duly packed his kit and left the ship at or just after 10:00. At about 14:00 hours, and within four hours of Henry's departure, HMS

Vanguard suddenly blew up at anchor, killing all but 20 of her crew of 838.

Henry survived the war and was pensioned off in 1938 having attained the rank of Chief Petty Officer, Torpedo Coxwain. However, the

Navy hadn't quite finished with him!

On 3rd September 1939, World War II broke out. Chief Petty Officer Henry Grew was called up from the Royal Navy Reserve and

served once more for the duration of the conflict.

PL 11 Wanderer

PL11 Wanderer" was a small Manx fishing Lugger of 18 tons. She was built in 1881 and owned by Charles Morrison of Peel. The

wanderer was the last Manx fishing boat to go to the fishing grounds in the Southern Ireland waters. The crew were Skipper, William

Ball, Stanley Ball, William Gale, Thomas Woods, Robert Watterson, Harry Costain and John MacDonald.The Wanderer was fishing,

seven miles off the Old head of Kinsale on that fateful day when the Lusitania was torpedoed. The story is best learned by words

wrote home by some of the crew.

The Skipper William Ball wrote.

“When we saw the Lusitania sinking, about 3 miles SSW of us, we made straight for the scene of the disaster. We picked up the first

people about quarter of a mile of where she sunk, and then we picked up about four boat loads of people. We couldn’t take any more,

as we had 160 –men, women and children on board. In addition to this, we towed two life boats full of passengers. We had a busy

time making tea for the people and we gave them a lot of clothes and a bottle of whisky we were leaving for our journey home. We

were the only boat there for two hours. The people were in a sorry sight, most of them having been in the cold water. We took them to

within two miles of the Old Head, when it fell calm. The tug boat Flying Fish from Queenstown then came up and took them from us. It

was an awful thing to see her sinking, and to see the plight of these people. I cannot describe to you in writing what we saw”

Crew member Thomas Woods, of Peel, was alone on watch and steering, when he saw the Lusitania list. He wrote; -

“It was the saddest thing I ever saw in all my life. I cannot tell you in words but it was a great joy to me to help the poor mothers and

babes in the best way we could.”

Youngest crewman Harry Costain said in his letter home:_

….We saw an awful sight on Friday. We saw the sinking of the Lusitania, and we were the only boat about at the time. We saved 160

people. and took them on our boat. I never want to see the like again. There were four babies about three months old, and some of

the people were almost naked - just as if they had come out of bed. Several had legs and arms broken, and we had one dead man,

but we saw hundreds in the water. I gave one of my changes of clothes to a naked man, and Johnny Macdonald gave three shirts and

all his drawers….

Stanley Ball:

….We saw the Lusitania going east. We knew it was one of the big liners by her four funnels, so we put the watch on. We were lying

in bed when the man on watch shouted that the four-funnelled boat was sinking. I got up out of bed and on deck, and I saw her go

down. She went down bow first. We were going off south, and we kept her away to the S.S,W. So we went out to where it took place -

to within a quarter of a mile of where she went down, and we picked up four yawls We took 110 people out of the first two yawls, and

about fifty or sixty out of the next two; and we took two yawls in tow. We were at her a good while before any other boat. The first

person we took on board was a child of two months. We had four or five children on board and a lot of women. I gave a pair of

trousers, a waistcoat, and an oil-coat to some of them. Some of us gave a lot in that way. One of the women had her arm broke, and

one had her leg broke, and many of them were very exhausted….

Each of the seven brave Manxmen received medals, one of silver for Skipper William Ball and six made of bronze for the crew, at the

open air Tynwald Ceremony at St. Johns on July 5th, 1915. They were presented, on behalf of the Manchester Manx Society, by the

Islands Lieutenant Governor, Lord Raglan. The medals all carried the same design, by F S Graves. On the obverse is a Viking ship,

below which is carried the words “For Service to the Manx People”. On the reverse, within a pattern of Celtic interlacing are four

crests with the wording; “Manchester Manx Society _ Son Ta Shin Ooilley Vraaraghyn” (for we are all brethren). Engraved round the

rim of each medal is the recipient’s name along with the words “Lusitania Rescue – May 7th 1915”

Lord Raglan the Lt. Governor said.

“The Manchester Manx Society voiced the sentiments of all Manx people when it invited the crew of the Wanderer to accept a medal

in remembrance of the fortunate act of charity and courage performed in going to the assistance of those whose lives that were so

cruelly destroyed by the blowing up of the Lusitania.”

All seven of the Wanderers crew were modest about the rescue. They seldom talked of the role they played on that fateful day when

they were casting nets within earshot of the Cunard liner.

Lord Raglan concluded “The heroism of the crew of the Wanderer will live as long as the tragic remembrance of the fate of the

Lusitania”

A very big thank you to Roy Baker, Curator of The Leece Museum on the Isle of Man for the above.

Comments and suggestions to admin@lusitania.net

The Sinking of R.M.S. Lusitania,

the rescue of survivors and the recovery of bodies.

The first section, Disaster, follows the events of "fateful Friday" from

11.00 in the morning to the time that the LUSITANIA sank beneath

the waves.

The second part, Rescue, has been written for the website using

information and images supplied by Thomas Brierley, Great-

Grandson of the Captain Brierley mentioned in the text, to whom

we are extremely grateful for this most personal of memories and

Dara Gannon, of the RNLI Lifeboat Station at Courtmacsherry,

Ireland.

A third section, Recovery operation, has now been added thanks to

information received from David Grew, the son of a late crew

member of the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Venus.

NOTE:

Any wireless instructions received by the LUSITANIA prior to 11.00

are not featured in the following excerpt but they are of course fully

dealt with in the books. What Captain Turner DIDN'T know at this

point, was that the Admiralty in London had WITHDRAWN his

escort (without telling him) due to the KNOWN presence of a U-

boat.

At this point in the story LUSITANIA was steering course South 87

East at 15 knots through thick fog, 25 miles off the south coast of

Ireland. Captain Turner was fully expecting to meet his naval

escort, the light cruiser HMS Juno, at any time.

DISASTER

Friday 7th May 1915

At 11.00, the Lusitania broke through the fog into hazy sunshine. To

port was an indistinct smudge, which was the Irish coastline.But

there was no sign of any other ships. No Juno.

Captain Turner increased the ship's speed to 18 knots. Barely had

he done this when a messenger from the Marconi room brought

him a signal. It was 12 words, but he did not recognize the cypher.

It was from Vice Admiral Coke in Queenstown.Because of the high-

grade code used to send the signal, he would have to take it down

to his day cabin to work on it.

At 11.55 there was a knock on Turner's door. It was the messenger

with another signal from the Admiralty; he broke off from his

decoding work to read it.

It said:

"SUBMARINE ACTIVE IN SOUTHERN PART OF IRISH

CHANNEL,LAST HEARD OF TWENTY MILES SOUTH OF

CONNINGBEG LIGHT VESSEL.MAKE CERTAIN LUSITANIA

GETS THIS."

This gave Captain Turner another problem. According to this latest

message,another U-boat was operating in the very middle of the

channel he was aiming for.If this were true,then despite his

Admiralty instructions,a mid channel course was now out of the

question. More than ever, he now had to determine his exact

position, if he was going to have to play a potentially deadly game

of cat and mouse with a U-boat in a narrow channel entrance. But

first he decided to finish deciphering Coke's earlier message.

By 12.10 he had finished decoding it completely. What he read

galvanised him.He went straight to the bridge and immediately

altered the ship's course 20 degrees to port.The turn to port was so

sudden that many passengers momentarily lost their balance. The

Lusitania was now closing to the land at 18 knots on course North

67 East. The clock on the bridge said 12.15, GMT. Atlantic Ocean,

22 miles off Waterford

The German submarine U-20 blew her tanks and surfaced. The fog,

which had been troubling her commander, Kapitan-Leutnant

Walther Schwieger, had finally cleared.

They were now down to the last three torpedoes and his orders

were to save two for the trip home,just in case they encountered an

enemy warship and had to fight their way out of it. Schwieger

checked his watch. It was 12.20 GMT as the U-20 headed back

toward Fastnet at full speed.

At 12.40, whilst Lusitania was still on course N67E,Turner received

another Admiralty signal.

This one read:

"SUBMARINE FIVE MILES SOUTH OF CAPE CLEAR,

PROCEEDING WEST WHEN SIGHTED AT 10 AM."

He allowed himself a slight smile. Cape Clear was many miles

astern of the eastbound Lusitania.

This latest signal effectively meant that the immediate danger was

passed.The entrance to St. George's Channel and therefore the

next notified U-boat threat,would still be four to five hours away, if

he had maintained his original heading.For now, he was safely in

the middle. As far as Captain Turner knew, there were NO U-boats

in his immediate vicinity.

At 13.20 GMT, U-20 was still running on the surface, heading back

toward Fastnet.Schwieger was up on the conning tower with the

lookouts. Suddenly, the starboard lookout saw smoke off the U-20s

starboard bow. Schwieger focussed his binoculars on it. One, two,

three, four funnels.He estimated the distance between them to be

12 to 14 miles. It would be a long shot, but if the ship was heading

for Queenstown,it might just be possible.

As the diving klaxon screeched out it's warning.U-20 altered course

to intercept the ship,submerging as she did so.

At 13.40 GMT, Captain Turner saw a landmark as familiar to him as

his own front door. A Long promontory with a lighthouse on top of it,

which was painted with black and white horizontal bands. The Old

head of Kinsale.

Now that he knew where he was, he ordered Lusitania's course

reverted to South 87 East, steady. He urgently needed to fix his

position,in order to plot a course to Queenstown. They were not

going to Liverpool after all, not yet anyway. The message from Vice

Admiral Coke which was sent in the high-grade naval code was

ordering him to divert Lusitania into Queenstown immediately.

Standard Admiralty practice in situations of grave peril.

Turning back to his officers on the bridge,he noticed the ship's

newest officer, whom he had christened Bisset (Junior Third Officer

Albert Bestic), due to go off watch in about 15 minutes. "Ah, Bisset.

Do you know how to take a four point bearing?" he asked. Bestic

certainly did. He also knew that it took the best part of an hour with

the ship's course and speed having to remain rock steady whilst it

was done. "Yes sir." He replied. "Good. Then kindly take one off

that lighthouse, will you?"

And with that Turner left the bridge and went into the chartroom.

Bestic needn't have worried. Lewis came back at 14.00 and

relieved him anyway, knowing what the "old man" had done.Bestic

took the first set of bearing figures to Will in the chartroom on his

way off the bridge.

Captain Turner calculated that they were now 14 miles offshore and

slightly West of the Old Head. He now had to plot a course through

the mine-free channel into Queenstown harbour.

Kapitan-Leutnant Walther Schwieger meanwhile, was studying the

big ship through U-20's attack periscope. Calling to the U-boat's

pilot, Schwieger said,"four funnels, schooner rig, upwards of 20,000

tons and making about 22 knots." Lanz, the pilot, checked in his

copies of Jane's fighting ships and Brassey's naval annual. Lanz

called back to Schwieger, "either the Lusitania or the Mauretania,

Herr Kapitan-Leutnant." (Both were listed in Brassey's as being

armed merchant cruisers). "Both are listed as cruisers and used for

trooping."

U-20 prepared for action. One G6 torpedo was loaded into a

forward tube. Schwieger then noticed the target altering course. He

could not believe his luck! He noted later in his logbook that "the

ship turns to starboard then takes a course to Queenstown....."

Exactly what he had hoped she would do!

At a range of 650 yards, Schwieger gave the deadly order, "Feur!"

There was a loud hiss, the U-boat trembled and Wiesbach, the

torpedo officer confirmed to Schwieger "Torpedo Los!" The G-Type

torpedo had cleared the tube and was streaking toward its intended

target at 38 knots with its running depth set at three metres, about

ten feet.

Meanwhile,

Captain Turner had come out of the chartroom and was standing

on the port side of the Lusitania's bridge. He was watching Lewis

working on the four-point bearing.Beyond him,stood a

Quartermaster right out on the bridge wing acting as a

lookout.There was another on the starboard bridge wing. But it was

from the crows nest that the sudden warning came,via the

telephone. "Torpedo coming on the starboard side!" The torpedo

struck the ship with a sound which Turner later recalled was "like a

heavy door being slammed shut." Almost instantaneously came a

second, much larger explosion, which physically rocked the ship. A

tall column of water and debris shot skyward, wrecking lifeboat No.

5 as it came back down.The clock on the bridge said 14.10.

Watching events through his periscope, Kapitan-Leutnant

Schwieger could not believe that so much havoc could have been

wrought by just one torpedo. He noted in his log that "an unusually

heavy detonation" had taken place and noted that a second

explosion had also occurred which he put down to "boilers, coal or

powder." He also noticed that the torpedo had hit the Lusitania

further forward of where he had aimed it. Schwieger brought the

periscope down and U-20 headed back to sea.

On the bridge of the Lusitania, Captain Turner could see instantly

that his ship was doomed. He gave the orders to abandon ship. He

then went out onto the port bridge wing and looked back along the

boat deck. The first thing he saw was that all the port side lifeboats

had swung inboard, which meant that all those on the starboard

side had swung outboard.The starboard ones could be launched,

though with a little difficulty, but the port side boats would be

virtually impossible to launch.

Panic by John Gray

Each of the wooden lifeboats weighed five tons unladen. To steady

them, each had a metal chain called a snubbing chain which held it

to the deck.Prior to lowering the boat, the release pinhad to be

knocked out using a hammer, otherwise the boat would remain

chained to the deck.

Beaching the ship was obviously out of the question. Turner knew

they were fourteen miles from shore and she was sinking so fast

that they'd never make it. He had to stop the ship so that the boats

could be safely lowered. Instinctively, he rang down to the engine

room for full speed astern.

The engine room dutifully complied but unfortunately, the overall

steam pressure had now dropped drastically, so the Lusitania's

massive turbines were virtually out of commission.At 14.11, the

Lusitania had started sending distress signals from the Marconi

room.

"SOS, SOS, SOS. COME AT ONCE. BIG LIST. 10 MILES SOUTH

OLD KINSALE. MFA."

The last three letters were the Lusitania's call sign.When Vice

Admiral Coke in Queenstown received his copyof that distress

signal,it must have seemed as thoughhis worst nightmare had

come true.

He had tried in vain all morning to obtaina firm decision from the

Admiralty in London. In the end, Coke had been so worried by the

obvious danger that he had taken it upon himself to divert the

Lusitania into Queenstown. Unfortunately, it was all too late.Still,

there was something he could do.He sent a signal to Rear Admiral

Hood in command of HMS Juno and sent him to the rescue. Coke

then sent a detailed signal to the Admiralty, advising them of what

had happened and of his actions. On the Lusitania, the list

indicator had just gone through the 15 degree mark.

Captain Turner was still out on the port side wing of the bridge. He

had ordered Staff Captain Anderson not to lower any of the boats

until the ship had lost a sufficient amount of her momentum to

render it safe.In some cases, on the port side, that meant getting

the passengers out of the lifeboats in order to lower them to the

rail. But the passengers did not want to get out of the boats.

At port side boat station no.2, junior Third Officer Bestic was in

charge. Standing on the after davit, he was trying to keep order

and explain that due to the heavy list, the boat could not be

lowered. Suddenly, he heard the sound of a hammer striking the

link-pin to the snubbing chain. Before the word "NO!" left his lips,

the chain was freed and the five-ton lifeboat laden with over 50

passengers, swung inboard and crushed those standing on the

boat deck against the superstructure.

Unable to take the strain, the men at the davits let go of the falls

and boat 2, plus the collapsible boat stowed behind it,slid down the

deck towing a grisly collection of injured passengers and jammed

under the bridge wing, right beneath the spot where Captain Turner

was.

Bestic, determined to stop the same situation arising at the next

boat station, jumped along to no.4 boat; just as somebody knocked

out it's linkpin. He darted out of the way as no.4 boat slid down the

deck maiming and killing countless more people, before crashing

into the wreckage of the first two boats.Driven by panic, assengers

swarmed into boats 6, 8, 10 and 12. One after the other they

careered down the deck to join 2 and 4.

The sea was now swirling over the bridge floor. Then Lusitania's

stern began to settle back and a surge of water flooded the bridge,

sweeping Captain Turner out of the door and off the ship.

As the Lusitania sank beneath the waves, that same surge of water

swept junior Third Officer Bestic out through the first class entrance

hall into the Ocean.

The Lusitania was gone, and with her had gone 1, 201 people. It

was now 14.28 GMT, on Friday 7th May, 1915.

REMINDER: You may wish to return to the page about Captain

Turner at this point, if you entered this page from there.

RESCUE.

At approx. 2.30pm, intelligence was received by Rev William

Forde; the then Hon Secretary of the Courtmacsherry Lifeboat

Station, that a large four funnel steamer was in distress South East

of the Seven Heads. Rev Forde immediately went to summon the

volunteer lifeboat crew. On his arrival at the Lifeboat Station, then

located at Barry’s Point he was met by the Coxswain and his crew.

At 3pm, the Courtmacsherry Lifeboat, Ketzia Gwilt under the

command of Coxswain Timothy Keohane (Father of Antarctic

explorer Patrick Keohane) was launched. In calm conditions, the

sails were of no use so the entire distance of approx. 12.6 nautical

miles to the casualty had to be rowed.

An extract from the original Courtmacsherry Return to Service log

states “We had no wind, so had to pull the whole distance – On the

way to wreck we met a ship’s boat cramped with people who

informed us the Lusitania had gone down. We did everything in our

power to reach the place but it took us at least 3 ½ hours of hard

pulling to get there – then only in time to pick up dead bodies”. The

Courtmacsherry Lifeboat then proceeded in picking up as many

bodies as they could and transferred them to the ships on scene

tasked with transferring bodies back to Queenstown.

The final entry from the return to service log written by Rev Forde,

who also joined the crew that day, reads: “Everything that was

possible to do was done by the crew to reach the wreck in time to

save life but as we had no wind it took us a long time to pull the 10

or 12 miles out from the boat house. If we had wind or any motor

power our boat would have been certainly first on the scene – It

was a harrowing sight to witness – The Sea was strewn with dead

bodies floating about, some with lifebelts on others holding on

pieces of rafts – all dead. I deeply regret it was not in our power to

have been in time to save some”.

Courtmacsherry Lifeboat stayed on scene engaged in the work of

recovering bodies, until 20.40Hrs when they were then towed back

to the entrance of Courtmacsherry bay by a Steam Drifter fishing

vessel. They partly rowed and partly sailed back the rest of

homeward journey,reaching the boat house at approx. 01.00Hrs on

8th May.

Meanwhile the Wanderer, a little fishing boat from the Isle of Man,

was among the first to reach the scene and they picked up about

200 survivors. Although they were in danger of sinking with the

overload, they still managed to take two of the Lusitania's lifeboats

in tow.

FLYING FISH seen here at the White Star pier in Queenstown.

She is on the extreme left of the picture, next to the jetty.

Captain Thomas Brierley, Master of the FLYING FISH.

The Wanderer was intercepted about two miles of the Old Head of

Kinsale by the Admiralty tug the Flying Fish, under the command of

Captain Thomas Brierley. The survivors were transferred to the tug

and taken to Queenstown (Cobh), under Admiralty orders. Captain

Brierley and the Flying Fish made several such trips, gathering and

ferrying survivors from the scene to Queenstown, and many of

those survivors owed their lives to him and his vessel. Most of the

rescue ships were sailing vessels of the local fishing fleet and

would have taken hours in the light winds prevailing that day to

reach the scene of the disaster, 12 miles offshore.The Flying Fish

was an old side-wheel paddle steamer built in 1886 at South

Shields. Although just 122 feet long, and affectionately known

amongst the locals in Queenstown as the "Galloping Goose", she

rendered a service that day which far outshone her diminutive size.

As well as serving as a tug, she was also used as a tender from

the White Star Line pier at Queenstown, taking passengers and

mail out to the waiting liners.Captain Thomas Brierley was born in

1859, not 1861 as shown in the image above and was 56 at the

time of the disaster. He was awarded a medal for the outstanding

gallantry he displayed during the endless trips he and his vessel

made back and forth from Queenstown, to where the Lusitania had

sunk. Bringing back the living, as well as the dead. What must

have been particularly frustrating to this gallant mariner, was the

fact that having heard of the disaster that had overtaken the

Lusitania, he had to wait, champing at the bit, for over an hour, for

Flying Fish to build up steam before they could head out to the

scene, knowing all the while that lives were being lost all that time.

Even after overcoming that obstacle, Captain Brierley found

himself caught up in red tape later when he tried to land survivors

at a pier not normally used by his vessel. He was kept waiting for

"official permission" to dock, for what must have seemed like an

eternity to him, when his only concern was to safely offload his

human cargo as quickly as possible so that he could return to the

scene and save more lives.

Captain Brierley died in 1920, aged just 61. He was buried in the

same area as many of the victims of the Lusitania disaster. Victims

that he personally had tried so hard to save from the jaws of death.

Clipping taken from the CORK EXAMINER

In this photo above, sailors from HMS Venus, an "Eclipse" class

cruiser belonging to the 11th Cruiser Squadron are helping to

unload recovered bodies from the rescue vessels in Queenstown.

The sailors are carrying the bodies to one of the many temporary

mortuaries that were set up in requisitioned buildings. Third from

right is 17 year-old Boy 1st Class Sailor Henry Grew temporarily

attached to H.M.S. Venus. (Lusitania Online)

The Recovery Operation.

On the afternoon of the disaster, the crews of the Royal Navy

cruisers that were based in Queenstown were put to work tending

to the injured

survivors and helping with the dead. The day after the disaster, the

Bluejackets were sent out aboard the Admiralty tugs Stormcock,

Warrior

and Flying Fish to recover bodies. Henry Grew was among those

sent to perform this grisly task. The bodies were brought back to

Queenstown

for subsequent burial in the mass graves that had been dug in the

old church cemetery.

Henry Grew also recovered the cushion seen here, which was

floating amid some bodies. He dried it out and kept it, eventually

passing it on to his son, David. David very kindly passed it on to

Lusitania Online in September 2003, for preservation. As for the

man who recovered the cushion, Henry Grew turned out to have

the luck of the Devil. On 27th May 1915, he returned to his own

ship the 19,250-ton "St Vincent" class Battleship HMS Vanguard.

He was with HMS Vanguard when the ship fought at Jutland and

both Henry and the ship came through the battle unscathed.

Thanks to our good friend Peter Boyd-Smith of "Cobwebs", we now

know that the cushion came from a sofa in the First Class Music

Room, located within the First Class Lounge on the Lusitania's

Boat Deck between funnels 3 and 4. On 1st November 2003,

Lusitania Online duly presented the cushion to the Merseyside

Maritime Museum for permanent display.

HMS Venus, seen here in 1899 visiting the French port of Rouen.

(Musee de Maritime Rouen).

Henry Grew, photographed just after he was

promoted to Ordinary Seaman aboard HMS Vanguard

(David Grew/Lusitania Online).

She was thereafter thought to be a "lucky ship" and certainly

Henry's former shipmates must have envied him his posting. On

the morning of July 9th 1917, after serving for a little over two years

on HMS Vanguard, Henry was routinely posted to HMS Pembroke.

He duly packed his kit and left the ship at or just after 10:00. At

about 14:00 hours, and within four hours of Henry's departure,

HMS Vanguard suddenly blew up at anchor, killing all but 20 of her

crew of 838.

Henry survived the war and was pensioned off in 1938 having

attained the rank of Chief Petty Officer, Torpedo Coxwain.

However, the Navy hadn't quite finished with him!

On 3rd September 1939, World War II broke out. Chief Petty

Officer Henry Grew was called up from the Royal Navy Reserve

and served once more for the duration of the conflict.

A final "signal" to the then 48 year-old CPO Grew from Admiralty.

(David Grew/Lusitania Online)

PL 11 Wanderer

PL11 Wanderer" was a small Manx fishing Lugger of 18 tons. She

was built in 1881 and owned by Charles Morrison of Peel. The

wanderer was the last Manx fishing boat to go to the fishing

grounds in the Southern Ireland waters. The crew were Skipper,

William Ball, Stanley Ball, William Gale, Thomas Woods, Robert

Watterson, Harry Costain and John MacDonald.The Wanderer was

fishing, seven miles off the Old head of Kinsale on that fateful day

when the Lusitania was torpedoed. The story is best learned by

words wrote home by some of the crew.

The Skipper William Ball wrote.

“When we saw the Lusitania sinking, about 3 miles SSW of us, we

made straight for the scene of the disaster. We picked up the first

people about quarter of a mile of where she sunk, and then we

picked up about four boat loads of people. We couldn’t take any

more, as we had 160 –men, women and children on board. In

addition to this, we towed two life boats full of passengers. We had

a busy time making tea for the people and we gave them a lot of

clothes and a bottle of whisky we were leaving for our journey

home. We were the only boat there for two hours. The people were

in a sorry sight, most of them having been in the cold water. We

took them to within two miles of the Old Head, when it fell calm.

The tug boat Flying Fish from Queenstown then came up and took

them from us. It was an awful thing to see her sinking, and to see

the plight of these people. I cannot describe to you in writing what

we saw”

Crew member Thomas Woods, of Peel, was alone on watch and

steering, when he saw the Lusitania list. He wrote; -

“It was the saddest thing I ever saw in all my life. I cannot tell you in

words but it was a great joy to me to help the poor mothers and

babes in the best way we could.”

Youngest crewman Harry Costain said in his letter home:_

….We saw an awful sight on Friday. We saw the sinking of the

Lusitania, and we were the only boat about at the time. We saved

160 people. and took them on our boat. I never want to see the like

again. There were four babies about three months old, and some

of the people were almost naked - just as if they had come out of

bed. Several had legs and arms broken, and we had one dead

man, but we saw hundreds in the water. I gave one of my changes

of clothes to a naked man, and Johnny Macdonald gave three

shirts and all his drawers….

Stanley Ball:

….We saw the Lusitania going east. We knew it was one of the big

liners by her four funnels, so we put the watch on. We were lying in

bed when the man on watch shouted that the four-funnelled boat

was sinking. I got up out of bed and on deck, and I saw her go

down. She went down bow first. We were going off south, and we

kept her away to the S.S,W. So we went out to where it took place

- to within a quarter of a mile of where she went down, and we

picked up four yawls We took 110 people out of the first two yawls,

and about fifty or sixty out of the next two; and we took two yawls

in tow. We were at her a good while before any other boat. The first

person we took on board was a child of two months. We had four

or five children on board and a lot of women. I gave a pair of

trousers, a waistcoat, and an oil-coat to some of them. Some of us

gave a lot in that way. One of the women had her arm broke, and

one had her leg broke, and many of them were very exhausted….

Each of the seven brave Manxmen received medals, one of silver

for Skipper William Ball and six made of bronze for the crew, at the

open air Tynwald Ceremony at St. Johns on July 5th, 1915. They

were presented, on behalf of the Manchester Manx Society, by the

Islands Lieutenant Governor, Lord Raglan. The medals all carried

the same design, by F S Graves. On the obverse is a Viking ship,

below which is carried the words “For Service to the Manx People”.

On the reverse, within a pattern of Celtic interlacing are four crests

with the wording; “Manchester Manx Society _ Son Ta Shin Ooilley

Vraaraghyn” (for we are all brethren). Engraved round the rim of

each medal is the recipient’s name along with the words “Lusitania

Rescue – May 7th 1915”

Lord Raglan the Lt. Governor said.

“The Manchester Manx Society voiced the sentiments of all Manx

people when it invited the crew of the Wanderer to accept a medal

in remembrance of the fortunate act of charity and courage

performed in going to the assistance of those whose lives that

were so cruelly destroyed by the blowing up of the Lusitania.”

All seven of the Wanderers crew were modest about the rescue.

They seldom talked of the role they played on that fateful day when

they were casting nets within earshot of the Cunard liner. Lord

Raglan concluded “The heroism of the crew of the Wanderer will

live as long as the tragic remembrance of the fate of the Lusitania”

A very big thank you to Roy Baker, Curator of The Leece Museum

on the Isle of Man for the above.

Almost identical lifeboat to the one sent out to the Lusitania from

Courtmacsherry. Photo; Dara Gannon, RNLI.

Copy of Courtmacsherry Lifeboat Station Log for 7th May 1915.

Photo: Dara Gannon, RNLI.

Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com