Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com

The Q-Ship was outwardly an innocent-looking merchant ship. (Like all other Merchantmen under Admiralty charter, the funnel was

painted black). In fact, a Q-Ship carried a naval crew, Royal Marines and concealed 4.1" guns. As a U Boat made a surface challenge

in accordance with the “Cruiser Rules”, the Q-Ship would obligingly stop. Sometimes they’d even lower a lifeboat in the pretence

of abandoning their ship. Then as the U Boat’s boarding party made its way over, the White Ensign would be suddenly unfurled and

the Q-Ship would open fire. The now highly vulnerable U Boat would be sent swiftly to the bottom in a hail of shell and rifle fire.

Q-Ships seldom took prisoners, as the crew of U27 discovered to their cost when they were attacked by the Q-ship Baralong.

Even the survivors from U27's crew were rounded up and murdered.

Contemporary cigarette card depicting Churchill's favourite weapon against U-boats:

The Q-Ship.

Mitch Peeke/Lusitania Online.

Room 40 at Admiralty House, London, was the hub of British Naval Intelligence. Tracking German Navy units was one of the main

efforts of Room 40. A large amount of the Wireless Telegraphy (W/T) traffic from, to and between submarines in the North Sea and the

Atlantic was regularly intercepted and deciphered by the British. Once decoded, this intelligence was passed directly on to the upper

echelons of the Admiralty; namely: First Sea Lord Jacky Fisher, First Lord Winston Churchill and Admiral Oliver.

Those three men needed to be fully aware of the very latest intelligence updates, particularly updates on the positions of German U-

boats. These were obtained by Naval Intelligence from Room 40’s wireless intercepts, from sighting reports and from the reports of

sinking's. Ultimately, it was those three men who made the operational decisions.

Background events leading up to the disaster

On Wednesday, 5th May, 1915, two days before the disaster, Churchill held a briefing in the Admiralty's war room. Unfortunately,

Fisher and Churchill were at odds over Churchill's disastrous Dardanelles campaign again. Fisher was harbouring a good deal of

resentment with Churchill's name on it, and Churchill himself was off to France that afternoon to participate in a Naval convention

which would bring Italy into the war on the side of the Allies. After that formality, he was to visit the Headquarters of Sir John French,

who was going to mount what would ultimately prove to be an equally disastrous offensive on the Aubers Ridge the following Friday, a

totally un-necessary diversion for Churchill.

One particular German U boat, U20, under the command of Kapitan-Leutnant Schwieger, was causing concern to those gathered in

the war room. She was known to be on her way toward Fastnet. Ever since she’d left her base, U20 had been giving her position to the

German Admiralty by Wireless Telegraphy every 4 hours. Unbeknownst to her commander, U20’s messages were being intercepted

and deciphered immediately by the Room 40 intelligence team.

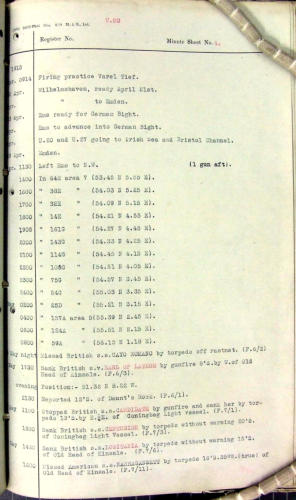

In fact, U20 had her own ledger at Room 40. That ledger is now in the National Archives at Kew, London. It is part of the ADM137

series. (The files ADM137/4152 are the U-boat history sheets compiled by Lt.Cdr. Tiarks).

Below is page 4 of U20’s Room 40 ledger from those files. It clearly shows that the British Admiralty had intercepted and decoded

EVERY message and sinking report from U20, right up to the sinking of the Lusitania. (In fact page 5 follows U20’s voyage home

afterwards, via her intercepted messages). It also clearly proves that those in charge at the Admiralty were FULLY INFORMED of

U20’s activities throughout her patrol.

U20 wasn’t the only vessel headed toward Fastnet. So was the Lusitania, and the cruiser due to escort her, HMS Juno. The U-boat

and the cruiser would arrive there ahead of the Cunarder. The three agreed that as HMS Juno, being of an obsolete design, was

particularly vulnerable to U-boat attack, it would be best for her to be immediately recalled to Queenstown. However, NO message

was sent to Captain Turner of the Lusitania to advise him that the escort he was expecting had now been cancelled. This was in case

the Germans intercepted the signal. The danger was there for all to see, but only the danger to the cruiser was apparently realised.

With that decision reached, the briefing was over. Churchill then had lunch with his wife, before he hurried off to Waterloo station to

catch his train. This left the Admiralty in the charge of First Sea Lord Jacky Fisher, who was aged 75 and sadly by then showing the

early signs of senility; and Admiral Oliver, who was deputising for Churchill whilst he was away.

Late that same Wednesday afternoon, U20 sank a small schooner, the Earl of Lathom off Kinsale. The Admiralty received separate

notification of the sinking by 21.30 that night, but as can easily be seen from the ledger page, they already knew about the Earl of

Lathom’s sinking when U20 sent a message to Germany at 17:30. By midnight, other news came in that the British Steamer Cayo

Romano had been unsuccessfully attacked off Queenstown (now Cobh) the night before. The ledger shows they intercepted U20’s

message about that BEFORE the Earl of Lathom was sunk. The only actions that were taken was the updating of U20's position on

the great map in the London war room, whilst the Naval base at Queenstown issued a general signal which said: "SUBMARINES

ACTIVE OFF SOUTH COAST OF IRELAND".

The next day, Thursday May 6th, U-20 sank two cargo ships, the Candidate and the Centurion, in the entrance to St. George's

Channel, near the Conningbeg lightship. She also unsuccessfully attacked the White Star liner Arabic By 11.00 on Thursday May 6th,

the Admiralty in London had confirmation of the sinking of the Candidate, though they didn't see fit to inform the Naval base at

Queenstown, Ireland, for a further 24 hours. By 03.40 on Friday, May 7th, they also knew the fate of the Centurion for certain.

Such is the background leading up to the morning of that fateful Friday. Now that you have this information, we can examine Churchill's

supposed "plan to get the Lusitania sunk".

Much has been made of his part in the disaster, largely based upon his supposed desire to purposefully have the Lusitania sunk and

so bring America into the conflict on the side of Britain. This would be achieved by the fact that American citizens regularly crossed the

Atlantic on the Lusitania and in the event of her destruction by a U Boat, some of them were bound to perish, thereby inflaming

American opinion, resulting in America subsequently declaring war on Germany. All this sounds wonderfully sinister, especially when

viewed in the light of the fact that Churchill was indeed actively seeking to embroil the U.S. with Germany, but there are a number of

holes in the argument which tend to rather scupper it, (to keep it in a nautical context), as we shall see later.

Although the Admiralty certainly had a pretty good appreciation of U20's whereabouts, there is A LOT of ocean off the South Coast of

Ireland. Secondly, the Lusitania the U-boat and would have had to be somehow guided to within a couple of miles of each other

without arousing the suspicion of anyone else at the Admiralty and, more importantly, without anyone arousing the curiosity of

Lusitania's Captain. Thirdly, Churchill would have needed to be absolutely certain that the U-boat Captain would indeed take the bait.

Given the recent advent of the Q-Ship and the fact that the Germans knew that British Merchant ships now had Admiralty instructions

to make a ramming attempt at any U-boat that challenged them, the U-boat Captain could have been equally suspicious of such an

apparently easy target.

Lastly, Churchill would have had to fulfil all three criteria in his absence. He did not return from France till the following Monday. When

he ended the briefing that Wednesday, all he KNEW was that U20 was heading for Fastnet and would get there at about the same sort

of time as HMS Juno. He wouldn’t at that point have been informed of anything other than U20’s failed attack on the Cayo Romano.

Whilst Churchill had undoubtedly considered the possibility of such an attack happening and how to use such a catastrophe to his own

best political advantage, to physically ENGINEER such a cataclysmic event was, we think, beyond even Churchill's capabilities. Even if

one considers Churchill's penchant for intrigues, and he certainly was actively intriguing against two other cabinet ministers at this time,

we do not consider that he could have carried out such a dastardly plan to fulfilment. He would then have been directly responsible for

the deaths of 1,201 men, women and children. The indelible stain of their blood would have been forever on his hands.

The only area where Churchill WAS guilty was in neglecting his duty by "going off on a jolly" as Fisher called it, and joining in with the

subsequent persecution of Captain Turner. He was not alone in this last action. Captain Richard Webb of the Admiralty Trade Dept.

and Admiral Oliver concocted the original case against Turner. Their problem was that the Lusitania had sunk in a mere 18 minutes

due to the explosion of the munitions that she was carrying on their behalf, after all measures of protection for her had been removed.

A scapegoat seemed to be urgently needed and who better to fill that position than the Liner’s Captain? They passed their contrived

report to Fisher to read. By the time he'd read it, he was livid, adding in the margin:

"Fully concur! As the Cunard company would not have employed an INCOMPETENT man, the certainty is absolute that Captain Turner

is not a fool, but a knave! It is my profound hope that Captain Turner will be arrested after the inquiry, whatever the outcome." (Fisher

always wrote in green ink!)

Once Churchill returned from France and read the report, he added: "Fully concur! We shall pursue the Captain without

check!"(Churchill always wrote in red ink! )

To borrow a phrase: "Who shall we hang so that we don't all hang together?" The answer, was Captain William Thomas Turner.

Comments and suggestions to admin@lusitania.net

Room 40 at Admiralty House, London, was the hub of British Naval

Intelligence. Tracking German Navy units was one of the main

efforts of Room 40. A large amount of the Wireless Telegraphy

(W/T) traffic from, to and between submarines in the North Sea

and the Atlantic was regularly intercepted and deciphered by the

British. Once decoded, this intelligence was passed directly on to

the upper echelons of the Admiralty; namely:First Sea Lord Jacky

Fisher, First Lord Winston Churchill and Admiral Oliver.

Those three men needed to be fully aware of the very latest

intelligence updates, particularly updates on the positions of

German U-boats. These were obtained by Naval Intelligence from

Room 40’s wireless intercepts,from sighting reports and from the

reports of sinking's.Ultimately, it was those three men who made

the operational decisions.

Background events leading up to the disaster

On Wednesday, 5th May, 1915, two days before the disaster,

Churchill held a briefing in the Admiralty's war room. Unfortunately,

Fisher and Churchill were at odds over Churchill's disastrous

Dardanelles campaign again. Fisher was harbouring a good deal

of resentment with Churchill's name on it, and Churchill himself

was off to France that afternoon to participate in a Naval

convention which would bring Italy into the war on the side of the

Allies. After that formality, he was to visit the Headquarters of Sir

John French, who was going to mount what would ultimately prove

to be an equally disastrous offensive on the Aubers Ridge the

following Friday,a totally un-necessary diversion for Churchill.

One particular German U boat, U20, under the command of

Kapitan-Leutnant Schwieger, was causing concern to those

gathered in the war room. She was known to be on her way toward

Fastnet. Ever since she’d left her base, U20 had been giving her

position to the German Admiralty by Wireless Telegraphy every 4

hours. Unbeknownst to her commander, U20’s messages were

being intercepted and deciphered immediately by the Room 40

intelligence team.

In fact, U20 had her own ledger at Room 40. That ledger is now in

the National Archives at Kew, London. It is part of the ADM137

series. (The files ADM137/4152 are the U-boat history sheets

compiled by Lt.Cdr. Tiarks).

Below is page 4 of U20’s Room 40 ledger from those files. It

clearly shows that the British Admiralty had intercepted and

decoded EVERY message and sinking report from U20, right up to

the sinking of the Lusitania. (In fact page 5 follows U20’s voyage

home afterwards, via her intercepted messages). It also clearly

proves that those in charge at the Admiralty were FULLY

INFORMED of U20’s activities throughout her patrol.

U20 wasn’t the only vessel headed toward Fastnet. So was the

Lusitania, and the cruiser due to escort her, HMS Juno. The U-boat

and the cruiser would arrive there ahead of the Cunarder.The three

agreed that as HMS Juno, being of an obsolete design, was

particularly vulnerable to U-boat attack, it would be best for her to

be immediately recalled to Queenstown. However, NO message

was sent to Captain Turner of the Lusitania to advise him that the

escort he was expecting had now been cancelled. This was in

case the Germans intercepted the signal. The danger was there for

all to see, but only the danger to the cruiser was apparently

realised.

With that decision reached, the briefing was over. Churchill then

had lunch with his wife, before he hurried off to Waterloo station to

catch his train. This left the Admiralty in the charge of First Sea

Lord Jacky Fisher, who was aged 75 and sadly by then showing

the early signs of senility; and Admiral Oliver, who was deputising

for Churchill whilst he was away.

Late that same Wednesday afternoon, U20 sank a small schooner,

the Earl of Lathom off Kinsale. The Admiralty received separate

notification of the sinking by 21.30 that night, but as can easily be

seen from the ledger page, they already knew about the Earl of

Lathom’s sinking when U20 sent a message to Germany at 17:30.

By midnight, other news came in that the British Steamer Cayo

Romano had been unsuccessfully attacked off Queenstown (now

Cobh) the night before. The ledger shows they intercepted U20’s

message about that BEFORE the Earl of Lathom was sunk.

The only actions that were taken was the updating of U20's

position on the great map in the London war room, whilst the Naval

base at Queenstown issued a general signal which said:

"SUBMARINES ACTIVE OFF SOUTH COAST

OF IRELAND"

The next day, Thursday May 6th, U-20 sank two cargo ships, the

Candidate and the Centurion, in the entrance to St. George's

Channel, near the Conningbeg lightship. She also unsuccessfully

attacked the White Star liner Arabic By 11.00 on Thursday May

6th, the Admiralty in London had confirmation of the sinking of the

Candidate, though they didn't see fit to inform the Naval base at

Queenstown, Ireland, for a further 24 hours. By 03.40 on Friday,

May 7th, they also knew the fate of the Centurion for certain.

Such is the background leading up to the morning of that fateful

Friday. Now that you have this information, we can examine

Churchill's supposed "plan to get the Lusitania sunk".

Much has been made of his part in the disaster, largely based

upon his supposed desire to purposefully have the Lusitania sunk

and so bring America into the conflict on the side of Britain. This

would be achieved by the fact that American citizens regularly

crossed the Atlantic on the Lusitania and in the event of her

destruction by a U Boat,some of them were bound to perish,

thereby inflaming American opinion, resulting in America

subsequently declaring war on Germany. All this sounds

wonderfully sinister, especially when viewed in the light of the fact

that Churchill was indeed actively seeking to embroil the U.S. with

Germany, but there are a number of holes in the argument which

tend to rather scupper it, (to keep it in a nautical context), as we

shall see later.

Although the Admiralty certainly had a pretty good appreciation of

U20's whereabouts, there is A LOT of ocean off the South Coast of

Ireland. Secondly, the Lusitania the U-boat and would have had to

be somehow guided to within a couple of miles of each other

without arousing the suspicion of anyone else at the Admiralty and,

more importantly, without anyone arousing the curiosity of

Lusitania's Captain. Thirdly, Churchill would have needed to be

absolutely certain that the U-boat Captain would indeed take the

bait.

Given the recent advent of the Q-Ship and the fact that the

Germans knew that British Merchant ships now had Admiralty

instructions to make a ramming attempt at any U-boat that

challenged them, the U-boat Captain could have been equally

suspicious of such an apparently easy target.

Lastly, Churchill would have had to fulfil all three criteria in his

absence. He did not return from France till the following Monday.

When he ended the briefing that Wednesday, all he KNEW was

that U20 was heading for Fastnet and would get there at about the

same sort of time as HMS Juno. He wouldn’t at that point have

been informed of anything other than U20’s failed attack on the

Cayo Romano.

Whilst Churchill had undoubtedly considered the possibility of such

an attack happening and how to use such a catastrophe to his own

best political advantage, to physically ENGINEER such a

cataclysmic event was, we think, beyond even Churchill's

capabilities. Even if one considers Churchill's penchant for

intrigues, and he certainly was actively intriguing against two other

cabinet ministers at this time, we do not consider that he could

have carried out such a dastardly plan to fulfilment. He would then

have been directly responsible for the deaths of 1,201 men,

women and children. The indelible stain of their blood would have

been forever on his hands.

The only area where Churchill WAS guilty was in neglecting his

duty by "going off on a jolly" as Fisher called it, and joining in with

the subsequent persecution of Captain Turner. He was not alone in

this last action. Captain Richard Webb of the Admiralty Trade Dept.

and Admiral Oliver concocted the original case against Turner.

Their problem was that the Lusitania had sunk in a mere 18

minutes due to the explosion of the munitions that she was

carrying on their behalf, after all measures of protection for her had

been removed. A scapegoat seemed to be urgently needed and

who better to fill that position than the Liner’s Captain? They

passed their contrived report to Fisher to read. By the time he'd

read it, he was livid, adding in the margin:

"Fully concur! As the Cunard company would not have employed

an INCOMPETENT man, the certainty is absolute that Captain

Turner is not a fool, but a knave! It is my profound hope that

Captain Turner will be arrested after the inquiry, whatever the

outcome." (Fisher always wrote in green ink!)

Once Churchill returned from France and read the report, he

added: "Fully concur! We shall pursue the Captain without check!"

(Churchill always wrote in red ink! )

To borrow a phrase: "Who shall we hang so that we don't all hang

together?" The answer, was Captain William Thomas Turner.

Contemporary cigarette card depicting Churchill's favourite

weapon against U-boats: The Q-Ship.

Mitch Peeke/Lusitania Online.

The Q-Ship was outwardly an innocent-looking merchant ship.

(Like all other Merchantmen under Admiralty charter, the funnel

was painted black). In fact, a Q-Ship carried a naval crew, Royal

Marines and concealed 4.1" guns. As a U Boat made a surface

challenge in accordance with the “Cruiser Rules”, the Q-Ship

would obligingly stop. Sometimes they’d even lower a lifeboat in

the pretence of abandoning their ship. Then as the U Boat’s

boarding party made its way over, the White Ensign would be

suddenly unfurled and the Q-Ship would open fire. The now highly

vulnerable U Boat would be sent swiftly to the bottom in a hail of

shell and rifle fire. Q-Ships seldom took prisoners, as the crew of

U27 discovered to their cost when they were attacked by the Q-

ship Baralong. Even the survivors from U27's crew were rounded

up and murdered.

Comments and suggestions to lusitaniadotnet@gmail.com